Introduction

The current political situation in many areas of Western and Central Asia makes effective ground based archaeological research virtually impossible. Whilst people are generally aware of the situation in Iraq, this is also true for Afghanistan and parts of Pakistan. Furthermore, since the mid-19th century, the mountainous regions that comprise the eastern borderlands of modern Afghanistan, along with the western parts of the North West Frontier Province (NWFP) and the Tribal Areas of modern Pakistan have been difficult to access for extended periods. However, with the widespread availability of free or inexpensive satellite imagery, it is now possible to 'visit' these regions by looking at them from space. The use of satellite imagery in this way has a number of specific archaeological applications, including the reconstruction of ancient routes, the remote detection of archaeological sites and the assessment of site destruction and looting.

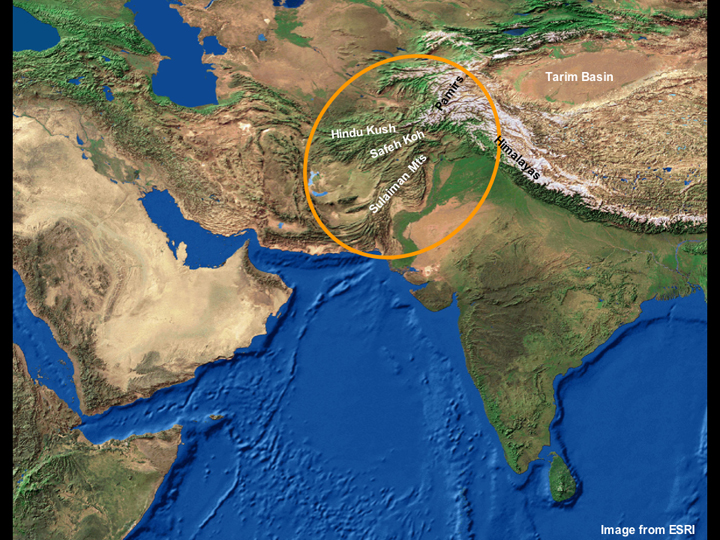

Stretching back into prehistory, the so-called Indo-Iranian borderland regions have acted as geographical (and cultural) barriers separating the peoples living in the plains of South Asia to the east, from those occupying the Iranian Plateau to the west, and the geographically varied regions of Central Asia to the north and East Asia to the northeast. The borderlands are dominated by a number of massive mountain ranges including the Himalayas, the Hindu Kush and the Safeh Koh, which are oriented roughly east-west, and the Pamirs and the Sulaiman Mountains, which are oriented roughly north-south.

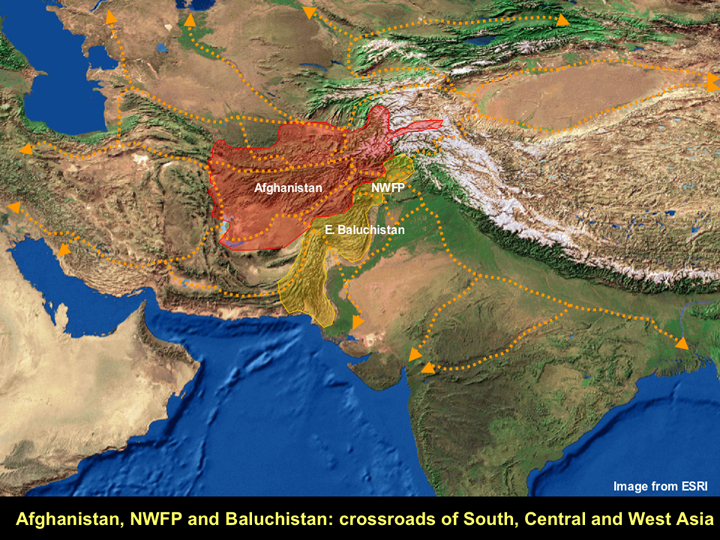

Although these major geographic features demarcate the landscape, the passes that intersect them facilitate the movement of people between north, south, east and west. It has long been acknowledged that the regions that now make up modern Afghanistan, and the NWFP and eastern Baluchistan in Pakistan acted as the 'Crossroads of Asia' (see Errington and Cribb 1992). While the passes through this region are mainly known for their role as components of the famous Silk Route (which was primarily in operation in the 1st and early 2nd millennia AD), from archaeological evidence of traded raw and finished materials we know that these routes were in use as far back as the Neolithic and the Bronze Age.

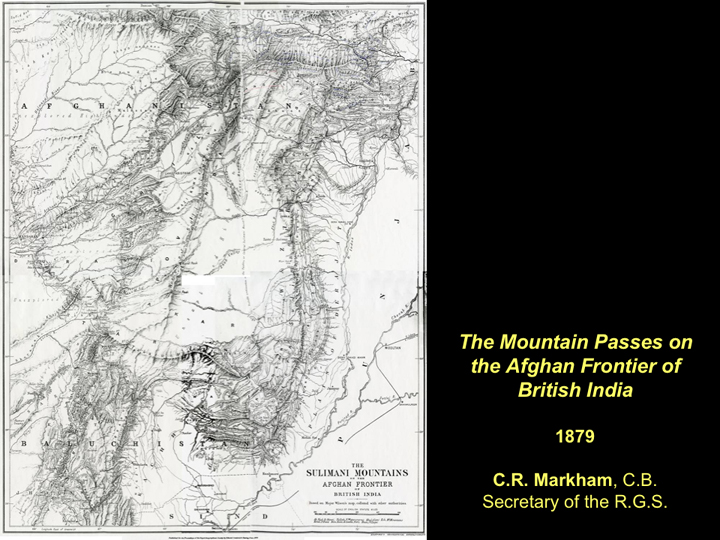

Up until the expansion of British interests into what was then western India and Afghanistan in the 19th century, there was relatively little recorded information about the routes that traversed these regions. This changed dramatically in the context of the imperial rivalry between Britain and Russia over Central Asia: the so-called Great Game (which is vividly recreated by Kipling in his novel Kim 1901: also see Hopkirk 1990). During this period, systematic exploration of much of Afghanistan and the Frontier Provinces was carried out, primarily under the guise of gathering military intelligence, and important gazetteers of passes and routes were compiled. An example of one of these reports is the list of major and minor passes traversing the Safed Koh and the Sulaiman Mountains that was compiled by the secretary of the Royal Geographic Society C.R. Markham (1879). This is the source of the map shown above.

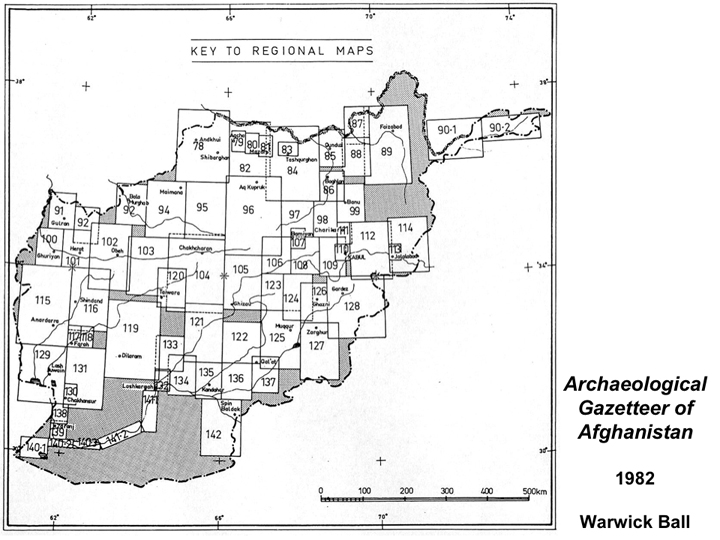

Beyond this information about the routes and modern peoples of these regions, it was not really until the major archaeological explorations of Afghanistan of the 20th century that our knowledge of the prehistory and early history of the region greatly expanded. Particularly in the period from the 1930s until the Soviet Invasion in 1979, there was considerable attention focussed on the archaeology of Afghanistan (Dupree 1977), which in many ways culminated in the compilation of a major gazetteer of archaeological sites throughout the country by Warwick Ball (1982). Subsequent, more detailed surveys focussing on Afghani Bactria have also been published (Gardin 1998; Gentelle 1989; Lyonnet 1997). Ball's volume included descriptions of archaeological sites and maps of varying levels of detail from most parts of Afghanistan, providing an essential record of the country's archaeological heritage.

With the Soviet Invasion and the three subsequent decades of turmoil, effective ground-based archaeological investigation in Afghanistan has virtually come to a complete standstill (see e.g. Thomas et al. 2006; Franke-Vogt et al. 2005 for exceptions). Furthermore, many unique sites like Bamiyan and Aï Khanoum have been subjected to deliberate destruction (in the case of the former) and systematic looting (in the case of the latter). This situation has by no means improved in the wake of the September 11th terrorist attacks and the subsequent invasion of Afghanistan – Operation Enduring Freedom.

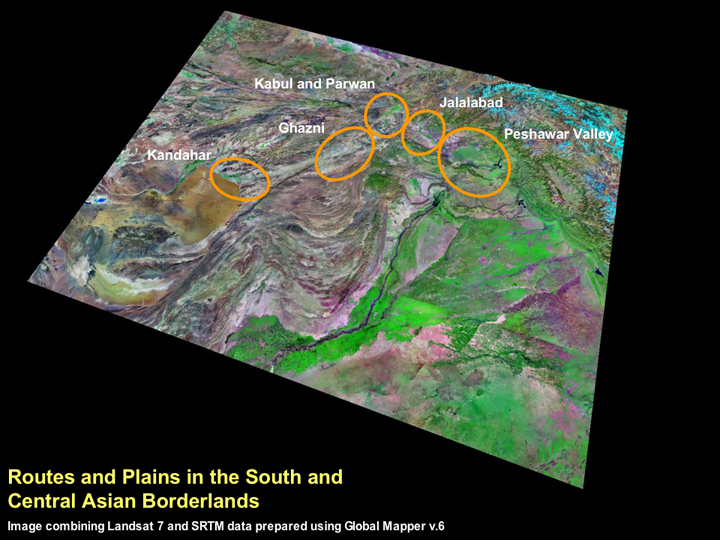

Although much of the borderlands are almost completely inaccessible for archaeological research on the ground, it is still possible to carry out research from space by using the readily available satellite imagery from NASA, such as the Landsat 7 and SRTM data that can be downloaded for free from the internet. Using GIS platforms such as ARCGIS and Global Mapper, it is possible to combine these data sets with information about the distribution of archaeological sites from Ball's (1982) gazetteer and other datasets of geographic information in order to:

- Reconstruct ancient routes and put them into a clear geographical context,

- Locate previously identified sites along those routes,

- Carry out remote sensing for previously undiscovered archaeological sites along those routes, and

- Assess the level of site destruction and looting at those sites that is visible from space.

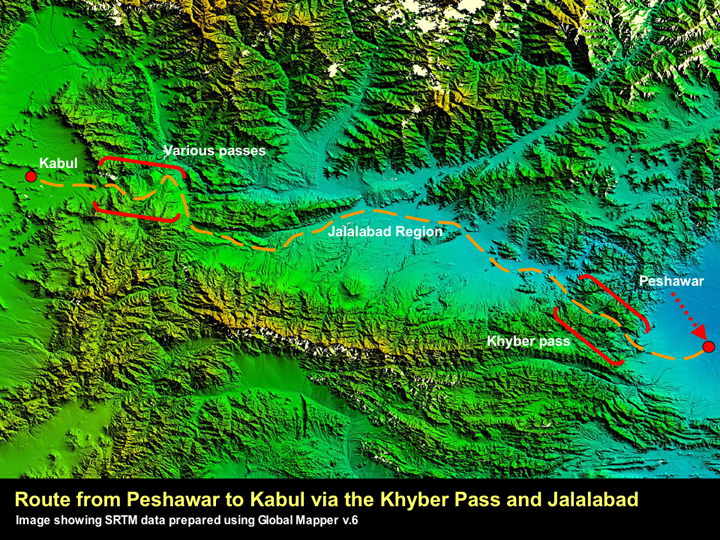

By combining Landsat 7 and SRTM data with Digital Chart of the World (DCW) data, and tracing the routes described by Markham (1879) and others, it is possible to broadly plot the main routes of access through the Safed Koh and the Sulaiman Range. These main routes are shown in red on the image above. It is apparent that these routes link together to form a network of paths providing passage between the east, the west, the north and the south. Many of the passes on these routes, such as the Khyber in the north and the Bolan in the south, are famous, but there are also other major passes including the Karana (which preceded the Khyber as the pre-eminent pass in the north), the Kurram, the Tochi, the Gomal and the Sanga. In addition to these major routes between the lowland and mountainous regions, there are also dozens of lesser passes that were used in the past (some of which are shown in orange).

This essay will to provide a basic introduction to some of the major plains in the NWFP and western Afghanistan, the routes that linked those plains, and some of the major archaeological sites of interest that are known from those regions. It is not a comprehensive analysis of the known routes and will be limited to the plains that lie along the route from the Peshawar Valley to Kabul, and those along the route from Kabul to Kandahar. Nonetheless, it will serve as a test case of the usability of readily available satellite imagery for investigating routes, plains and preservation.

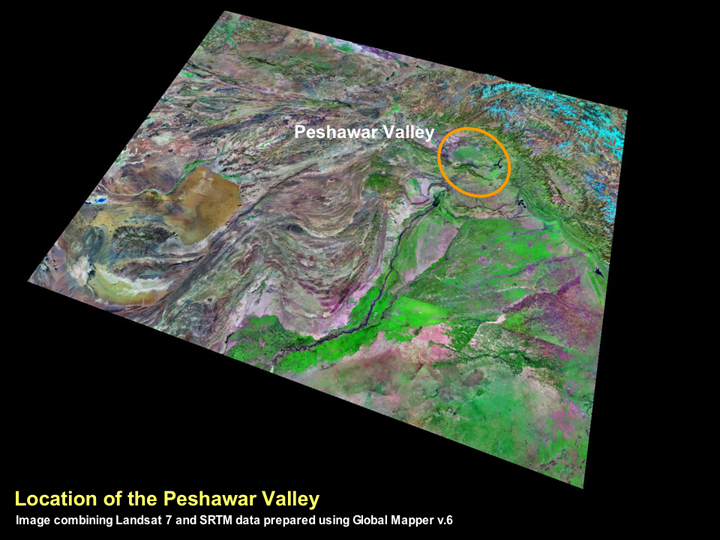

The Peshawar Valley lies at the extreme north-west corner of South Asia and for millennia it has served as a gateway between the rich plains of the subcontinent and the various regions of Central Asia.

The Peshawar Valley is effectively the main northern gateway into Afghanistan. There are several routes that head east out of the valley, but undoubtedly the most famous is the Khyber Pass, which is believed to have first come into heavy use during the Kushan Period (early 1st millennium AD), and today continues to be the main overland route between Peshawar and Kabul.

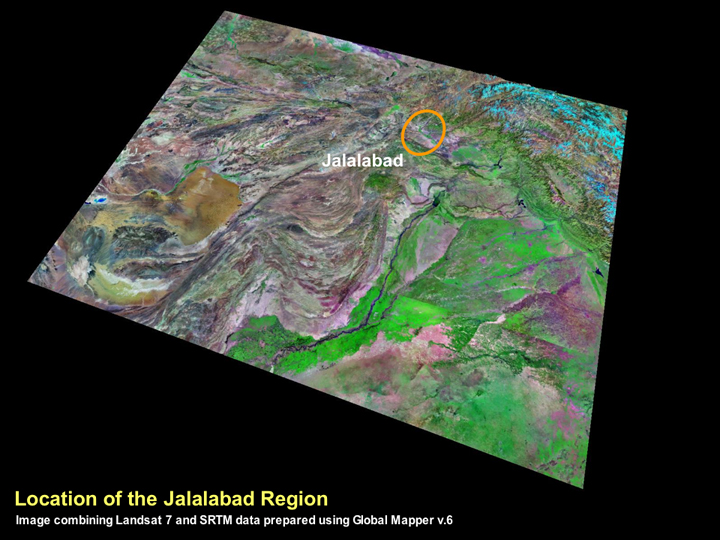

The Khyber Pass is in fact only the first stage of the approximately 240km route between Peshawar and Kabul, and it actually provides the key passage between the Peshawar Valley and the Jalalabad region. It is from the latter that further passes such as the Sokhta, Chinar and Haft Kotal must be traversed in order to reach Kabul (Markham 1897: 42). This entire route has been highlighted on the artificially coloured SRTM above, which very effectively emphasises the mountainous nature of the landscape.

The Jalalabad region has played a key role in the control of the Peshawar-Kabul route up to the present. It is notable that after the massacre of the British garrison of Kabul in 1842, only one of the 16000 people who had left Kabul with Major-General William Elphinstone managed to escape to the British garrison at Jalalabad (for a lively account of this see Hopkirk 1990: 266ff.).

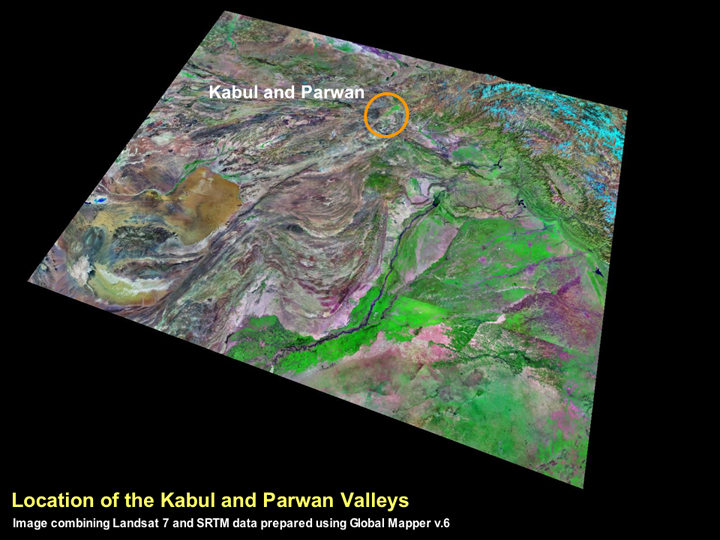

For millennia, the valleys of Kabul and Parwan have been home to the capitals of the northern part of highland Afghanistan. This is undoubtedly because in many respects, these adjoining valleys are the northern hub of the country, and have ready access to routes that radiate out to the north, south east and west.

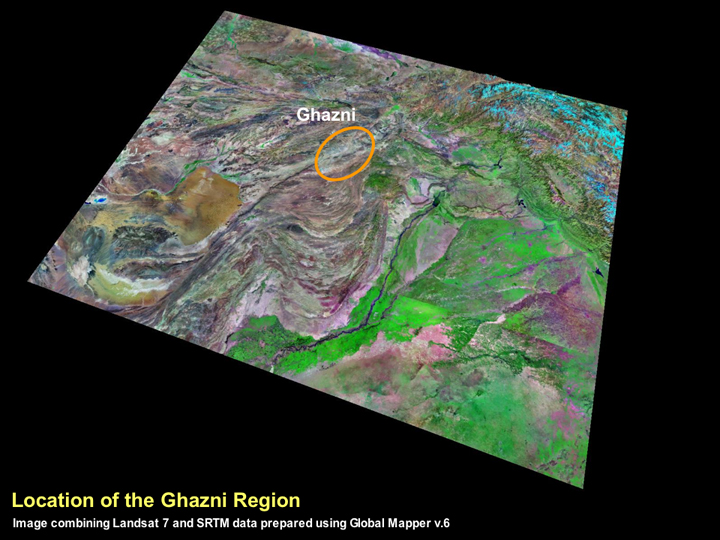

Ghazni ►

The city of Ghazni first came to major prominence in the 10th and 11th centuries AD as the capital city of the Ghaznavid Sultans. Subuktigin and his son Mahmud of Ghazni are renowned for their aggression and their role in the expansion of Islamic control into South Asia, particularly their repeated attacks on the Hindu Shahi kings who had formerly controlled a vast kingdom stretching from Kabul to the Peshawar Valley.

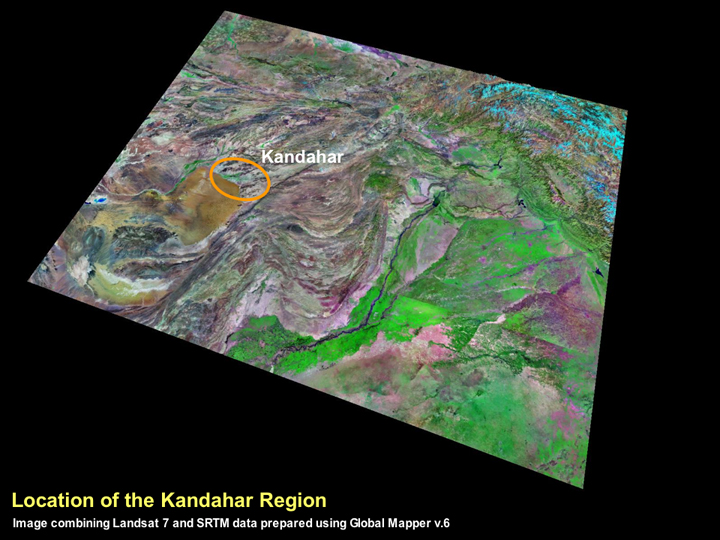

Kandahar ►

Kandahar and its neighbouring regions have very clear evidence for human settlement stretching back into prehistory, particularly at the sites of Deh Morasi Ghundai and Mundigak, which appear to have been first occupied in the 4th millennium BC (Dupree 1963; Casal 1961), contemporaneous with the village occupation at the Neolithic sites of Mehrgarh and Kili Gul Mohammad in Pakistani Baluchistan. One of the major urban sites of Central Asia stands at Kandahar itself, the site of Shahr-i Kohna or Old Kandahar (McNicoll and Ball 1996; Helms 1997), which is of a scale akin to the mound at Begram and the Bala Hisar at Charsadda.

Concluding Remarks

This essay has been a simple (and in some ways a simplistic) introduction to what in reality needs to be a major undertaking. Some initial work on compiling archaeological gazetteer data for Afghanistan using GIS has already been attempted by Mariner Padwa of Harvard University (see http://www.silk-road.com/newsletter/vol2num2/Evolving.html Silk Road Newsletter), but this still appears to be at the stage of data aggregation and cleaning. Nevertheless, there are several ways forward in using satellite imagery to assess issues of routes, plains and preservation in Afghanistan and the borderlands regions of Pakistan. What follows are a number of suggestions for how this might be achieved.

- Integration of Warwick Ball's complete Afghan Archaeological Gazetteer database (digitised by Andrew Sherratt and Toby Wilkinson) and other known data sets such as the surveys conducted in Bactria by the French (see Gardin 1998; Gentelle 1989; Lyonnet 1997).

- Integration of the complete South Asian site gazetteer (digitised by Gregory Possehl and Justin Morris and corrected by Randall Law)

- Detailed modelling of all routes through the mountains, combined with an assessment of the intervening plains

- Comparison of settlement gazetteer data and satellite data to see which sites are visible, and which are not (new sites?)

- Assessment of relevant Corona and higher resolution imagery to improve the resolution for the above.

Acknowledgements

I would like to especially thank Susan Sherratt for organising an excellent workshop, for inviting me to participate and for taking such pains to ensure that the ArchAtlas will both continue and thrive. I would also like to thank Toby Wilkinson for providing data at the eleventh hour, Debi Harlan for making this page 'live', and the other participants of the workshop for making the day in Sheffield truly stimulating.

This is dedicated to Andrew Sherratt – a man of dizzying intellect and boundless inspiration, who quickly detected my love of maps and found it very easy to twist my arm.

Occasional Papers (2009-)

Occasional Papers (2009-) Site Visualisations

Site Visualisations