Pathways and Highways

Department of Archaeology, University of Sheffield

SATURDAY, 7th MARCH 2009

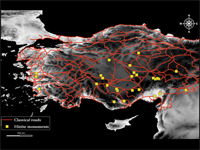

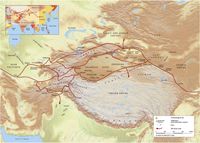

Toby Wilkinson & Sue Sherratt

It has long been recognised that the exchange of goods, people and ideas is instrumental in social change through human history. Archaeological accounts have tended to be one of two types: (1) material-led analyses of the distributions of objects, aided by scientific provenance studies; or (2) more general theoretical approaches addressing the possible mechanisms of exchange based on ideas from anthropology and economics. While both have been successful in recognising patterns in the material, and critiquing assumptions of our modern worldview, the missing factor has often been the mechanisms of movement, and the specific routes by which such exchanges could have taken place. A detailed understanding of the landscapes within which past peoples moved is thus necessary. Though there are significant challenges, this is increasingly becoming possible with GIS and remote sensing data, where the opportunities of advanced mapping combining multiple datasets allow archaeologists to return to the specificity of the landscape, rather than an abstract notion of space. They also make it possible to take account of both phenomenological understandings of landscape and map-based mathematical approaches to terrain and environment. The participants in this workshop showcase their work on routes, and address a set of questions on the importance of routes to exchange, and the ability of archaeology to solve such problems: