Developing out of collaborative fieldwork in the Mamasani Region of Fars, this interpretative essay was compiled between January and July 2005, while Cameron Petrie was the Katherine and Leonard Woolley Junior Research Fellow at Somerville College, Oxford, and developed as part of the ArchAtlas project to use satellite imagery and terrain modelling in studying patterns of ancient settlement and inter-regional contact.

1) Some of the most powerful and influential states and empires that came into being in ancient West Asia originated in what is now southwest Iran – including the Persian Empires ruled by the Achaemenid (c.539-330 BC) and Sasanian Dynasties (c. AD 125-630) and the various Elamite polities that engaged in warfare, political intrigue and trade with Babylonia and Assyria during the Bronze and Iron Ages (c.2200-641 BC). Southwest Iran was also the heartland of the so-called "Proto-Elamite horizon", which saw the first appearance of urbanism and pictographic writing in Iran, the latter of which appears to have spread from the southwest into the furthest reaches of the Iranian plateau in the late 4th mill BC (c.3300-2900 BC).

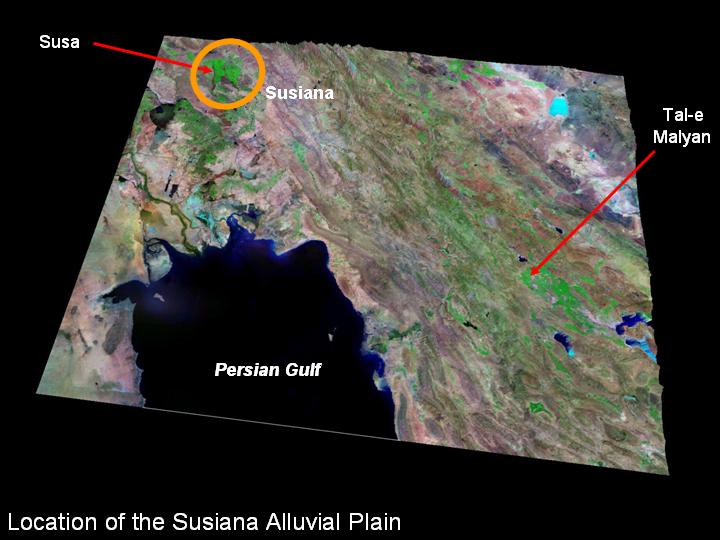

This image shows two key sites, Susa and Chogha Mish in the plain of Susiana (modern Khuzestan), which are shown in more detail below (images 8, 9-16).

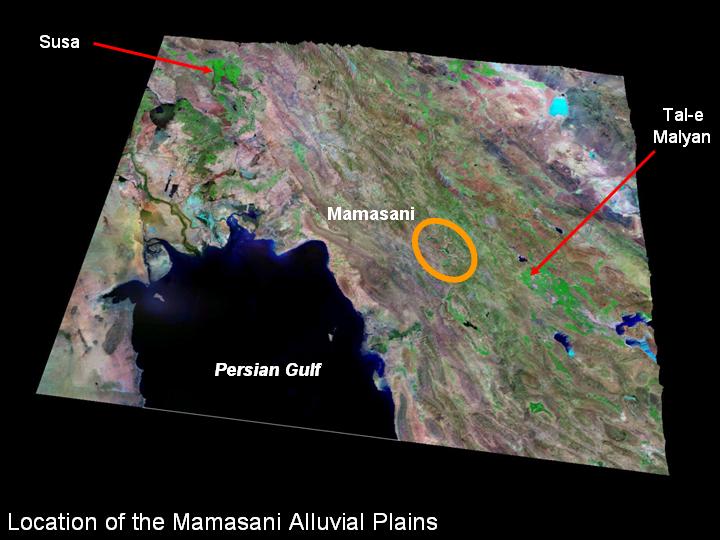

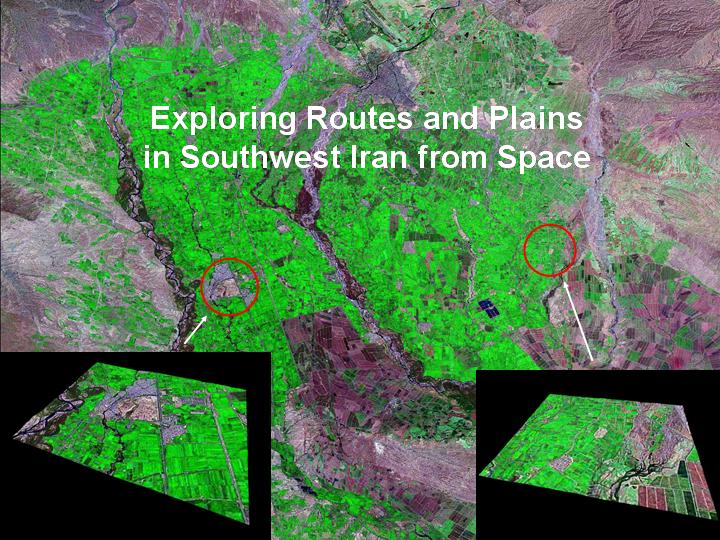

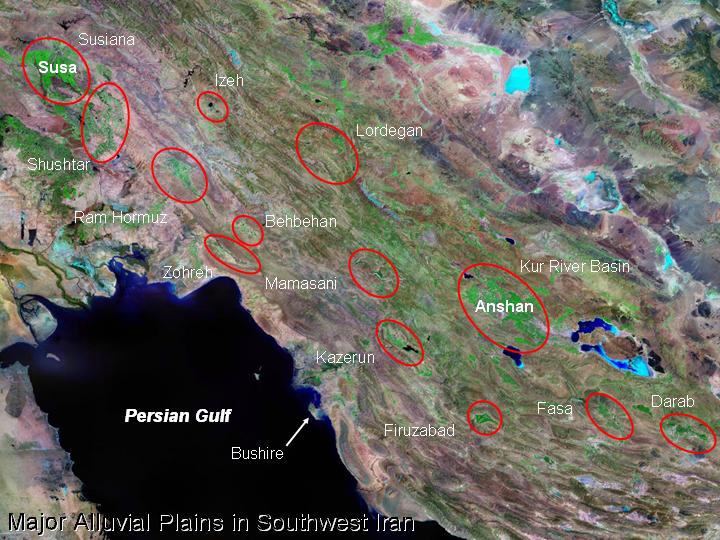

2) Satellite imaging provides a new dimension to fieldwork in the varied terrain of Southwestern Iran, where the folds of the Zagros Mountains separate the lowland plains of Khuzistan (which abut Mesopotamia) from the highland plains of Fars. Successive ridges enclose fertile intermontane valleys, and many of these fertile enclaves were settled as early as the Palaeolithic and appear to have a continuous history of occupation from the Neolithic down to the present day. A number of these valleys gained a historical importance as stepping stones on routes through the mountains (both for transhumance and trade), and as nodal points in the formation of political units. These intermontane valleys have also been the focus of several archaeological projects, and the inter-relations between them can now be seen all the more clearly from space.

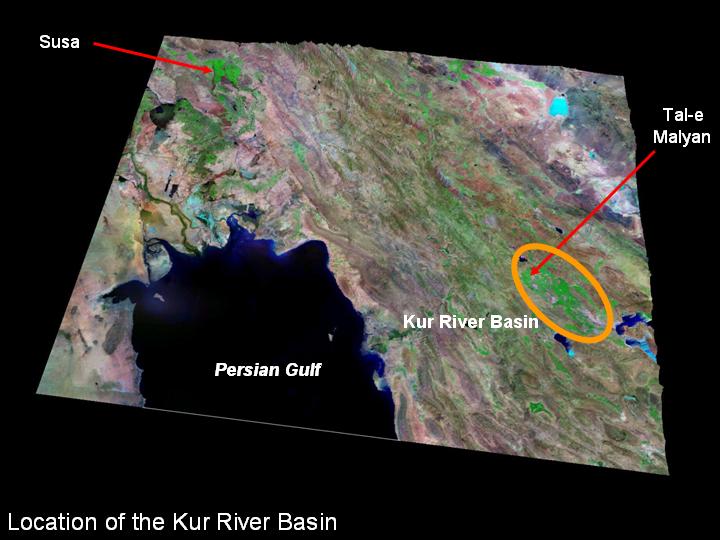

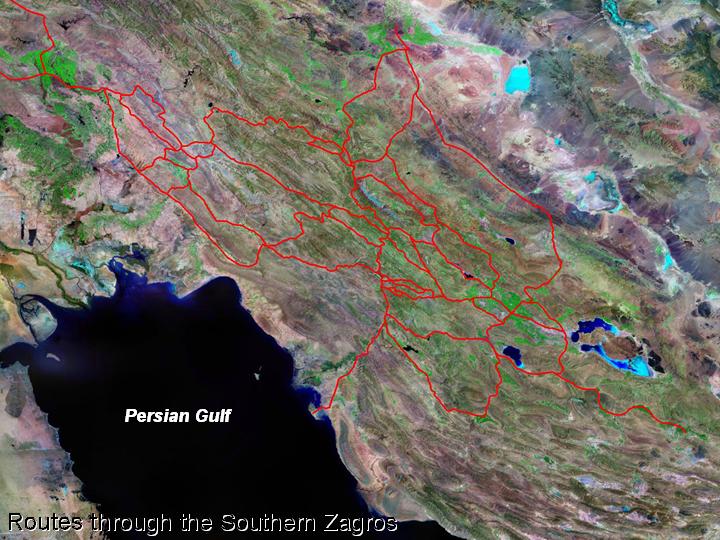

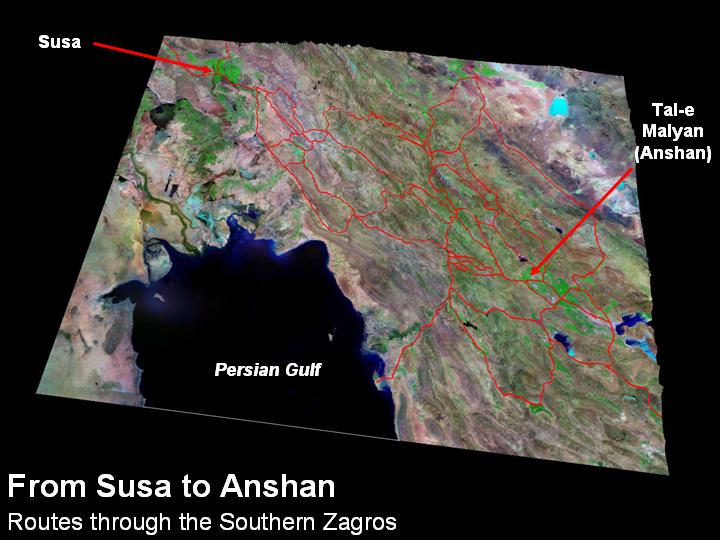

3) A defining characteristic of a number of the prehistoric and historic political entities in Southwest Iran was their dominance of both the lowland plains of Susiana and the highland Kur River Basin. During the late 3rd and 2nd millennium BC, these were referred to respectively as Susa and Anshan after their capital cities. Between these two regions, and also in various other areas in the southern Zagros, there are other, smaller intermontane valleys that were created during the formation of the Zagros, and which have been filled with alluvium and colluvium produced by later erosion.

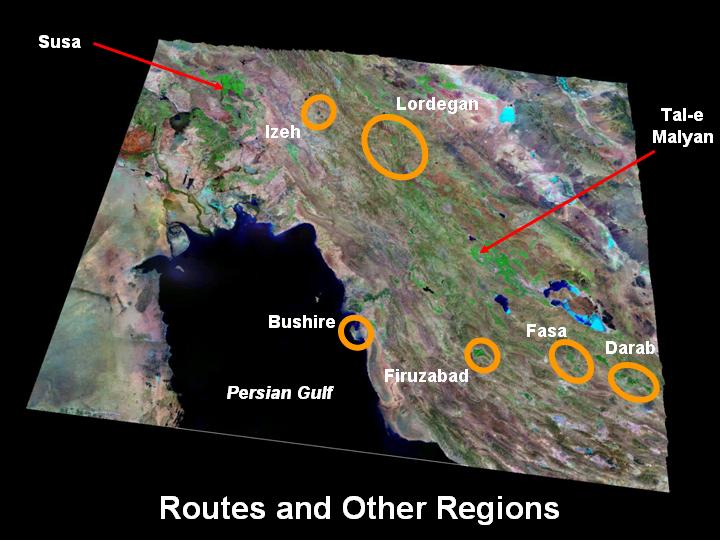

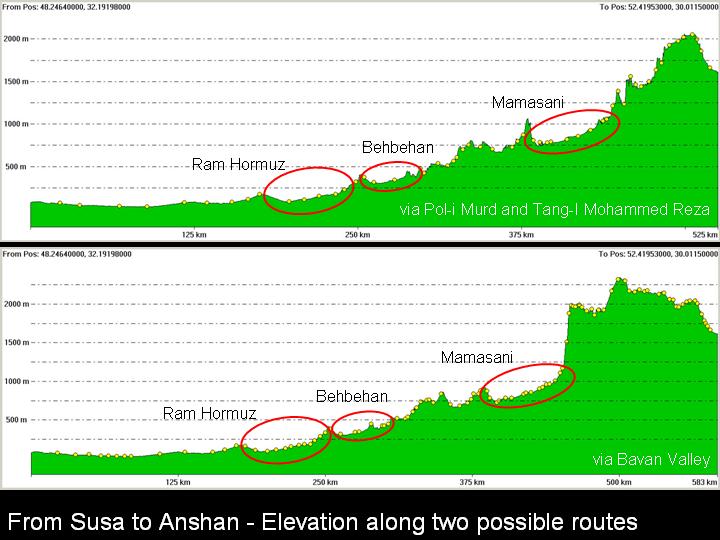

4) From the early 8th millennium BC, there is evidence for agriculture and stock-raising in the Central Zagros, and this has been used to suggest that herders were exploiting the varying environmental conditions of the Zagros at this time, by making use of the lowland alluvial plains in winter and highland plains in the summer (Hole 1996; 1998). The successful use of these environmentally distinct highland and lowland areas depended on the routes of passage and communication through the mountains, and there are only a limited number of routes which provide access through this range. While there are a limited number of routes In the southern Zagros, there are a number of routes that could have been used to travel between any two locations.

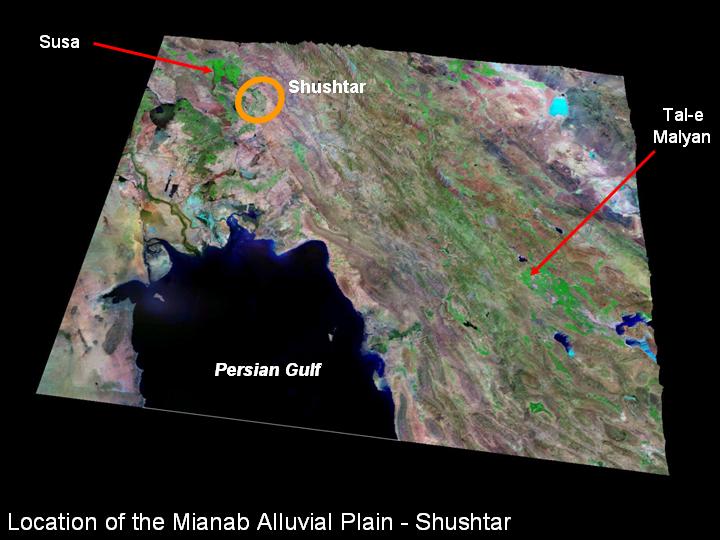

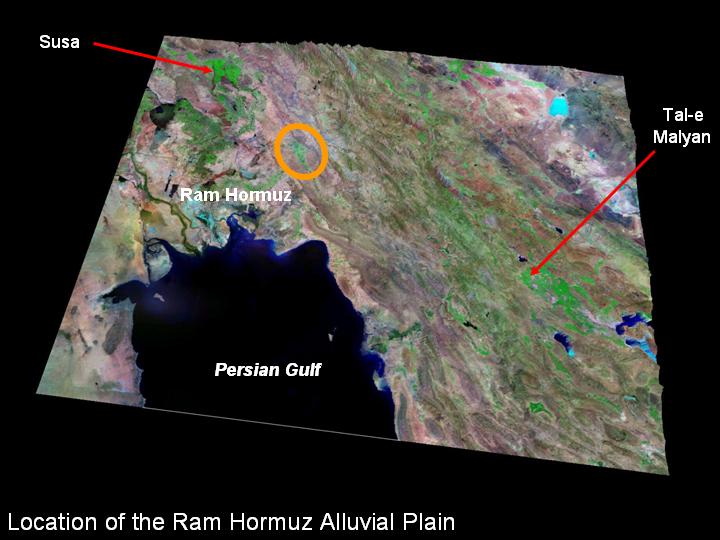

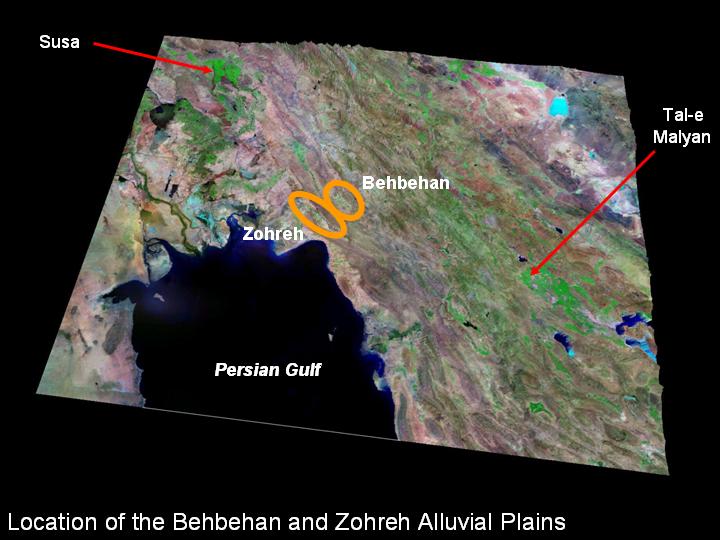

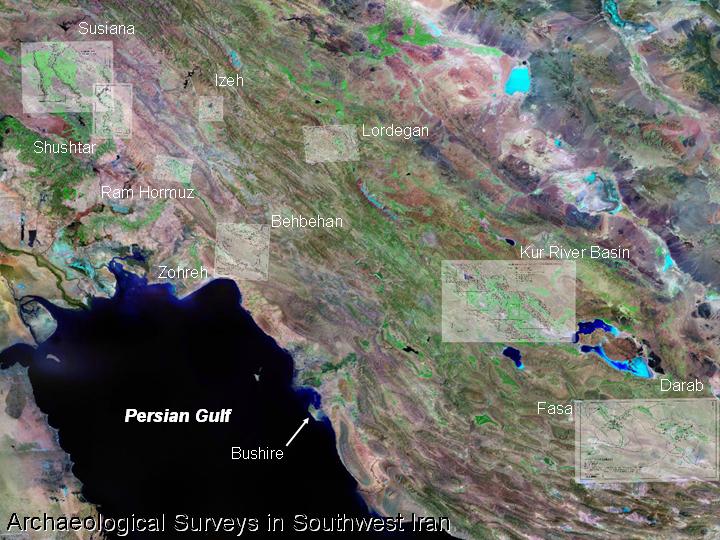

5) Extensive archaeological surveys have been undertaken on the Susiana Plain and in the Kur River Basin. These are the two largest plains in this part of Iran, and these surveys have provided insight into the dynamics of settlement in these regions. Additional surveys have also been carried out in the Ram Hormuz, Behbehan, Zohreh, Fasa, Darab, Izeh and Lordegan regions, and more recently, a number of intermontane plains have been investigated by Iranian archaeologists. Surveys are currently being carried out in the Shushtar and Mamasani regions and on the coast adjacent to Bushire. Most of the major alluvial plains have been investigated in some form during the last century.

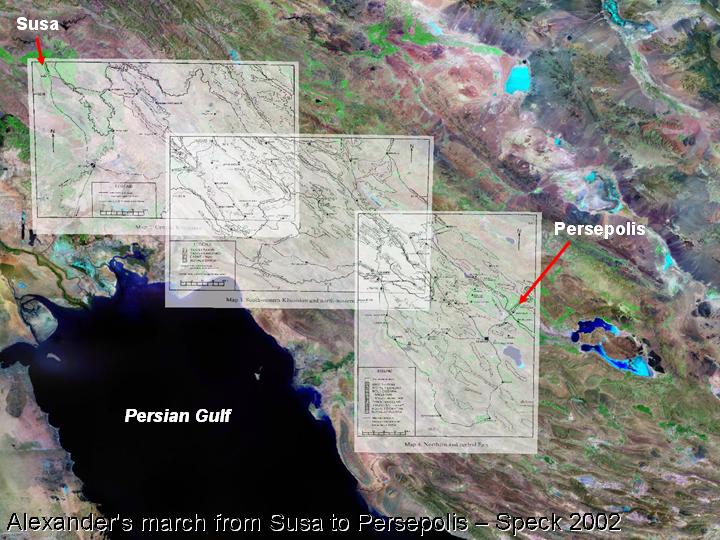

6) There have been a number of attempts to reconstruct the route taken by Alexander on his march between Susa and Persepolis in 330 BC (e.g. Stein 1936; MacDermott and Schippman 1999). Most recently, a comprehensive assessment of the possible routes has been published by Henry Speck (2002), based on first hand investigations that he made of the region during the 1970s, when he was trying to identifying the location of the so-called Persian Gates. He has argued that this pass was situated close to Yasuj, which differs from most previous assessments that assume that it was located close to Mamasani.

7) During the late 3rd and 2nd millennium BC, the two ancient capitals of southwest Iran were Susa and Anshan. While Susa had been identified as modern Shush in the 19th century, the site of Anshan was only located in 1970, when inscribed bricks were discovered on the surface of Tal-e Malyan, in the Kur River Basin (see Potts 1999; Reiner 1973). These two cities lay over 500 kms apart, and it was possible to travel between them by following one of a number of routes through the mountains. The decision by NASA to release a range of satellite imagery, as well as the 90m resolution SRTM digital elevation data, has provided an ideal opportunity to look at these plains and routes in a new way.

In the following images, each of the major valleys or plains between Susa and Anshan will be examined, beginning with the Susiana Plain. Clicking on the links gives access to a sequence of images for the relevant area.

8) The Susiana Plain makes up a large part of the province of Khuzistan, and geologically it is an extension of the Mesopotamian alluvial plain.

Click to access SETTLEMENT ON THE SUSIANA PLAIN (images 9-16)

17) Immediately to the east of the Susiana Plain is the Mianab alluvial plain, and the city of Shushtar.

Click to access SHUSHTAR (MIANAB PLAIN) (see images 18-19)

20) The Mianab Plain at Shushtar effectively marks the edge of lowland Khuzistan. To the southeast, the next major alluvial plain is Ram Hormuz, which is situated in the Zagros foothills.

Click to access RAM HORMUZ PLAIN (images 21-22)

23) Further to the southeast lie the plain of Behbehan, and the adjacent plain along the banks of the Zohreh River, which also lie in the Zagros foothills.

Click to access BEHBEHAN AND ZOHREH PLAINS (images 24-28)

29) The Ram Hormuz and Behbehan regions lie below 500 m above sea level, but the next series of alluvial plains, which lie in the region called Mamasani, are situated between 850 and 1000 m above sea level, and are surrounded by high mountain ridges.

Click to access MAMASANI PLAINS (images 30-33)

34) The largest of the alluvial plains in the southern Zagros is the Kur River Basin. This is the location of the highland capital of Anshan, which is known to have been situated at the site of Tal-e Malyan in the 3rd and 2nd millennia BC.

Click to access THE KUR RIVER BASIN (images 35-40)

41) The major route from Susa to Anshan is via the Ram Hormuz, Behbehan and Mamasani Plains. From Mamasani, there are a number of options of routes to Tal-e Malyan. As can be seen above, different routes traverse different landscapes, and also reach different altitudes.

42) In addition to the alluvial plains that lie on the major route between Susa and Anshan, there are also a number of other subsidiary plains in southwest Iran that have also been subjected to archaeological survey.

Click to access

BUSHIRE (images 43),

FIRUZABAD (images 44-46),

IZEH (images 52-55),

FASA AND DARAB (images 47-51),

LORDEGAN (images 56-63)

This interpretative essay developed out of collaborative research in the Mamasani Region of Fars, being carried out by the Iranian Centre for Archaeological Research (ICAR) of the Iranian Cultural Heritage and Tourism Organisation (ICHTO) and the University of Sydney. This research project is directed by Professor D.T. Potts of the University of Sydney and Mr. Kourosh Roustaei of the ICAR/ICHTO, and in addition to the support of these two institutions, it has been made possible thanks to funding from the Australian Research Council, Somerville College and the Faculty of Oriental Studies Oxford, the British Institute of Persian Studies, and the Iran Heritage Foundation.

The imagery and text was compiled between January and July 2005, while I was the Katherine and Leonard Woolley Junior Research Fellow at Somerville College, Oxford. The routes through southwest Iran presented in this study are far more comprehensive, thanks to the inclusion of the work of Henry Speck (2002). I would like to thank Andrew Sherratt for encouraging me to present this information in an electronic format, and inspiring me with his work using SRTM and LANDSAT data in Turkey and the Khabur, and also Toby Wilkinson for implementing the web presentation.

Bibliography

Adams, R.McC., 1962, Agriculture and Urban Life in Early Southwestern Iran, Science 136: 109-122.

Alizadeh, A., 2003, Excavations at the Prehistoric Mound of Chogha Bonut, Khuzestan, Iran: Seasons 1976/77, 1977/78 and 1996, Oriental Institute Publications, University of Chicago

Alizadeh, A., Kouchoukos, N., Wilkinson, T.J., Bauer, A.M., and Mashkour, M., 2004, Human-environment interactions on the Upper Khuzestan Plains, Southwest Iran. Recent investigations, Paléorient 30/1: 69-88.

Caldwell, J. R., 1968, Tell-i Ghazir, Reallexikon der Assyriologie und Vorderasiatishcen Archaologie F-G: 348-355.

Delougaz, P. and Kantor, H. J., (Eds.), 1996, Chogha Mish Volume 1: The First Five Seasons of Excavations 1961-1971, Oriental Institute Publications 101, Oriental Institute, Chicago.

Dittman, R., 1984, Eine Randebene des Zagros in der Frühzeit: Ergebnisse des Behbehan – Zuhreh surveys, Berliner Beiträge zum Vorderen Orient Band 3, Dietirch Reimer, Berlin.

Duschene, J., 1986, La localisation de Huhnur, in de Meyer, L., Gasche, H., Vallat, F. (eds.), Fragmenta historiae Elamicae: mélanges offerts à M.J. Steve, editions Recherche sur les civilisations: 65-74.

Hole, F., 1996, The context of caprine domestication in the Zagros region, in Harris, D.R., (ed.), The Origins and Spread of Agriculture and Pastoralism in Eurasia, UCL Press, London: 263-281.

Hole, F., 1998, The spread of agriculture into the eastern arc of the Fertile Crescent: food for the herders, in Damania, A.B., Valkoun, J., Willcox, G., and Qualset, C.O., The Origins of Agriculture and Crop Domestication: The Harlan Symposium, FAO, ICARDA, IPGRI.

Johnson, G. A., 1973, Local Exchange and Early State Development in Southwestern Iran, Archaeological Papers 51, Museum of Anthropology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Kouchoukos, N., and Hole, F., 2003, Changing estimates of Susiana's prehistoric settlement. In N. Miller & K. Adbi, eds., Yeki bud, Yeki nabud: Essays on the Archaeology of Iran in Honor of William M. Sumner, Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, UCLA.

MacDermott, B.C. and Schippman, K., 1999, Alexander's March from Susa to Persepolis, Iranica Antiqua 34: 282-308

Miroschedji, P. d., 1972, Prospections archéologiques dans de vallées de Fasa et de Darab. , Proceedings of the 1st Annual Symposium of Archaeological Research in Iran 1972, Tehran Ministry of Culture and Arts.

Miroschedji, P. d., 1974, Tepe Jalyan, une necropole du IIIe millenaire av. J.-C. au Fars oriental (Iran), Arts Asiatiques XXX: 19-64.

Moghaddam, A., and Miri, N., 2003, Archaeological Research in the Mianab Plain of Lowland Susiana, South-western Iran, Iran 41: 99-138.

Negahban, E.O., 1991, Excavations at Haft Tepe, Iran, University Museum Monograph 70, University Museum, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Potts, D. T., 1999, The Archaeology of Elam: formation and transformation of an ancient Iranian state, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

Reiner, E., 1973, The location of Anšan, Revue d'Assyriologie et d�archéologie Orientale 67: 57-62.

Speck, H., 2002, Alexander at the Persian Gates. A Study in Historiography and Topography, American Journal of Ancient History, New Series 1.1: 7-234.

Stein, M.A., 1936, An Archaeological Tour in the Ancient Persis, Iraq 3: 111-225.

Stein, M. A., 1940, Old Routes of Western Iran, Macmillan and Sons, London.

Stronach, D., 2003, The tomb of Arjan and the history of southwest Iran in the early soxth century BCE, in Miller, N.F. and Abdi, K., (eds.), Yeki bud, yeki nabud: Essays on the archaeology of Iran in honor of William M. Sumner, Los Angeles: 249-259.

Sumner, W. M., 1972, Cultural Development in the Kur River Basin, Iran: an archaeological analysis of settlement patterns, PhD, Pennsylvania.

Sumner, W. M., 1989, Anshan in the Kaftari Phase: Patterns of Settlement and Land Use, in Archaeologia Iranica et Orientalis: Miscellanea in Honorem Louis Vanden Berghe, de Meyer, L. and Haerinck, E., (eds.), Gent: 135-161.

Sumner, W. M., 2003, Early Urban Life in the Land of Anshan: Excavations at Tal-e Malyan in the Highlands of Iran, Malyan Excavations Reports III, University Museum Monograph 113. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Pennsylvania.

Vanden Berghe, L., 1954, Archaeologische navorsingen in de omstreken van Persepolis, Jaarbericht Ex Orient Lux 13: 394-408.

Whitcomb, D., 1971, The Proto-Elamite Period at Tal-i-Ghazir, Iran, M.A., thesis, Department of Archaeology, University of Georgia.

Wright, H.T., (ed.), 1979, Archaeological Investigations in Northeastern Xuzestan, 1976, Technical Reports Number 10, Research Reports in Archaeology Contribution 5, Museum of Anthropology, The University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Wright, H.T., and Carter, E., 2003, Archaeological Survey on the Western Ram Hormuz Plain: 1969, in Miller, N.F. and Abdi, K., (eds.), Yeki bud, yeki nabud: Essays on the archaeology of Iran in honor of William M. Sumner, Los Angeles:

Zagarell, A., 1982, The Prehistory of the Northeast Bahtiyara Mountains, Iran: The Rise of a Highland Way of Life, Beihefte zum Tübinger Atlas des Vorderen Orients, Ludwig Reichhert, Wiesbaden.

Occasional Papers (2009-)

Occasional Papers (2009-) Site Visualisations

Site Visualisations