Download a longer PDF version of this paper

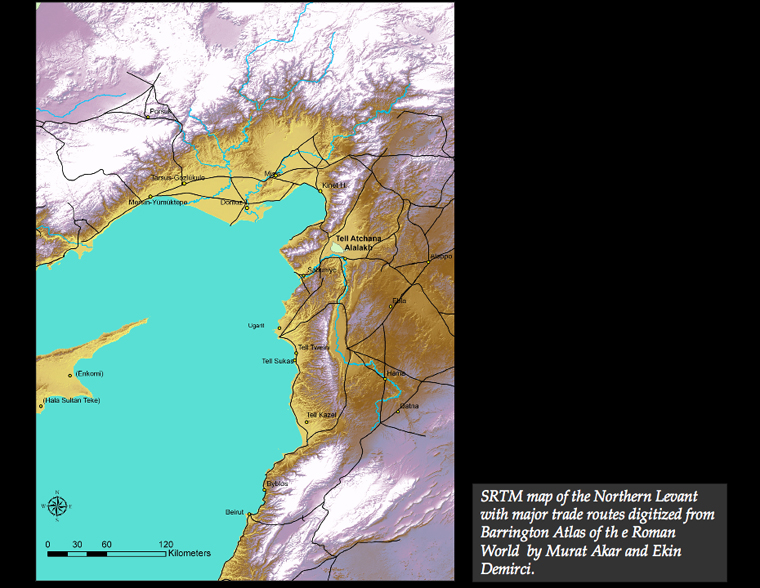

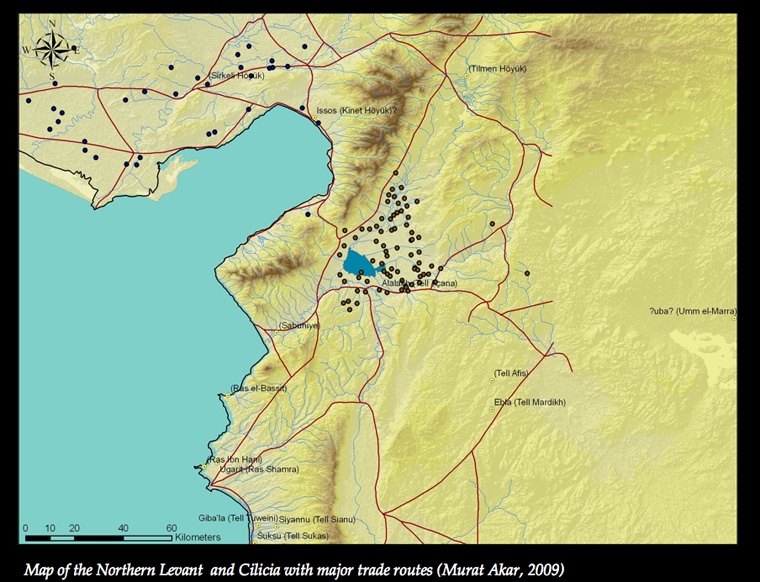

Trading connections and routes play a very important part in the development (or re-development) of urban centres in the Middle Bronze Age Levant. This is particularly clear in the regions of Cilicia and the Amuq Plain in the Hatay, in the north-east corner of the East Mediterranean, where at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age we have evidence of large-scale public buildings and fortification systems which represent the revival of complex political and economic structures, following a collapse at the end of the Early Bronze Age. A key role in this is played by harbour towns on the Cilician and Levantine coasts, which have an important part in the articulation and exploitation of maritime and inland routes connecting different zones and their resources. This in turn leads, by the beginning of the Late Bronze Age, to the formation of a symbiotic network of semi-dependent kingdoms which link these different inland and coastal zones in a single interactive socio-economic system.

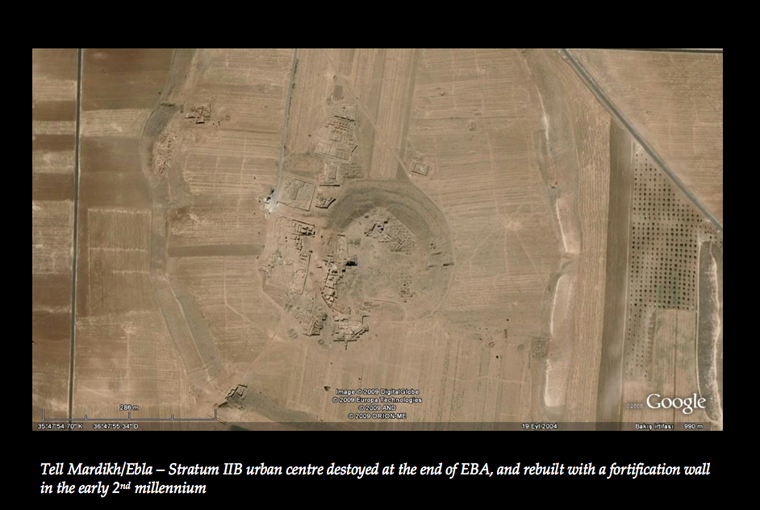

The factors that provoked the collapse of the Early Bronze Age centres, such as Ebla in inland Syria, are still debated. However, the collapse is evident in abandonment levels and signs of depopulation at major centres in inland and western Syria and in eastern Cilicia.

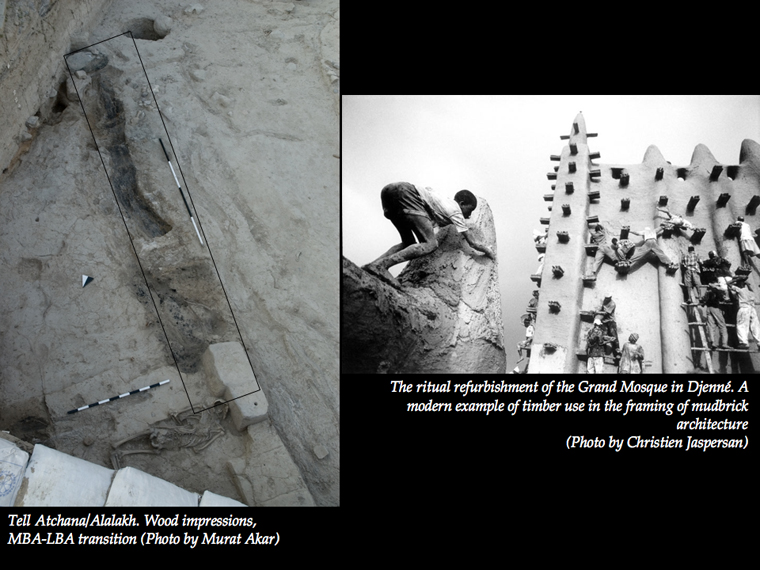

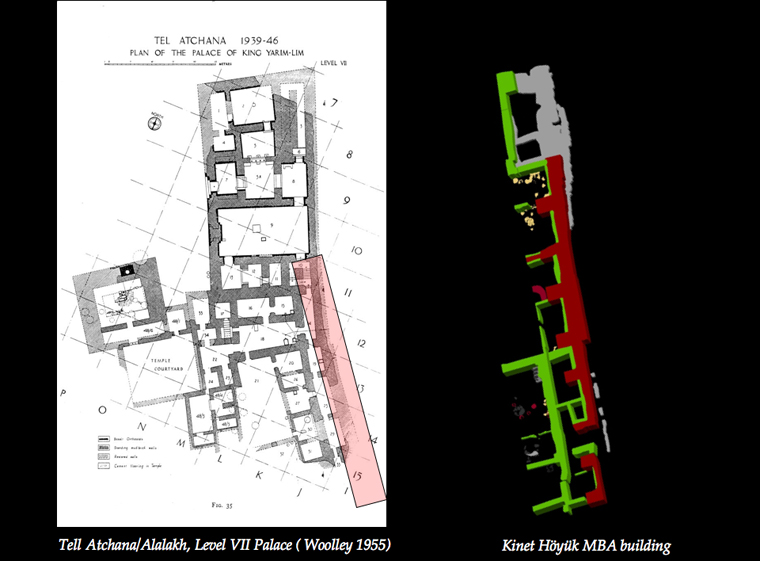

The Middle Bronze Age regeneration is indicated by large fortified cities and palace complexes in the MB II levels at various sites, which provide evidence of an organized political and economic system able to acquire large quantities of non-local resources. A case in point is the use of long wooden planks in the roofing and timber-framing of mudbrick architecture, as seen here at Tell Atchana (Alalakh) in the Amuq Plain, which may be compared with the use of timber-framing in modern monumental buildings, such as the Grand Mosque at Djenné in Mali. This represents a heavy demand for timber, which in the more treeless regions of the east made cities dependent on external sources and may have led to the development of specialised ports which owed their existence to the handling of such supplies. Metals are another similar example. Much of the importance of the harbour town of Kinet Höyük, which lies between the rich timber and metal resources of the Taurus and Amanus mountains, may have lain in the part it played in shipping both to other parts of the Levant. In mediaeval times, the port of Hisn-al Tinat, a later successor of Kinet Höyük, was used for the shipment of timber from the Amanus for export to Egypt, southern Syria and Tarsus in Cilicia.

Other materials, such as iron – which is recorded in the Middle Bronze Age Kültepe archives as worth 30-40 times the value of silver – had special significance for conspicuous consumption among the elite, and acted as an important stimulus to the development of commercial contacts and trading routes. They may also have encouraged individual enterprise and possibly even the rise of a form of 'black market' to circumvent elite attempts to maintain exclusivity. Texts from the Old Assyrian trading colony at Kültepe in Central Anatolia list the penalties for trading forbidden materials such as iron, which suggest that such trading took place quite frequently.

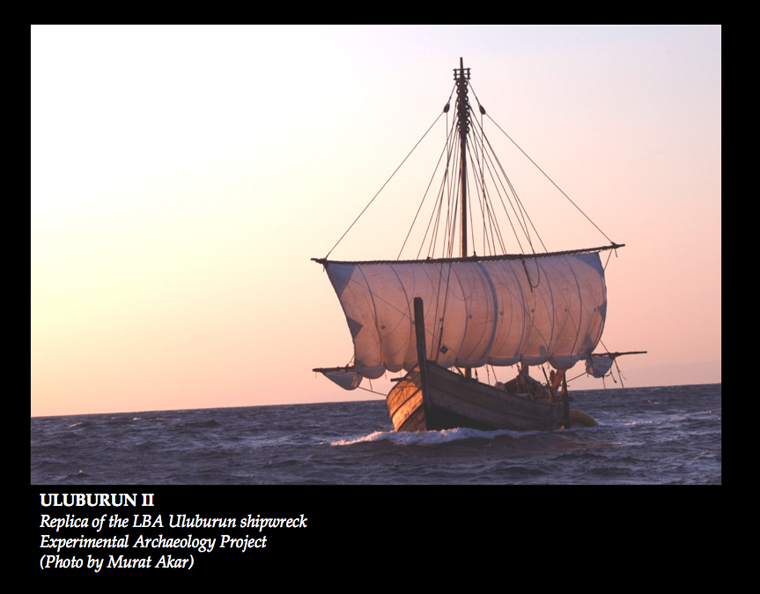

Technological advances in sailing and ship building were almost certainly developed and exploited in this highly competitive environment. Iconographical evidence and the evidence of stone anchors suggest that the large round-hulled merchant ships of the type familiar from a painting in the 18th Dynasty tomb of Kenamun in Egypt and from the remains of the 14th century BC Uluburun wreck (replica shown here) were already plying the East Mediterranean in the Middle Bronze Age. It is probably only a matter of time before the wreck of a Middle Bronze Age cargo ship, similar to that of Uluburun off the coast of southern Turkey, is found.

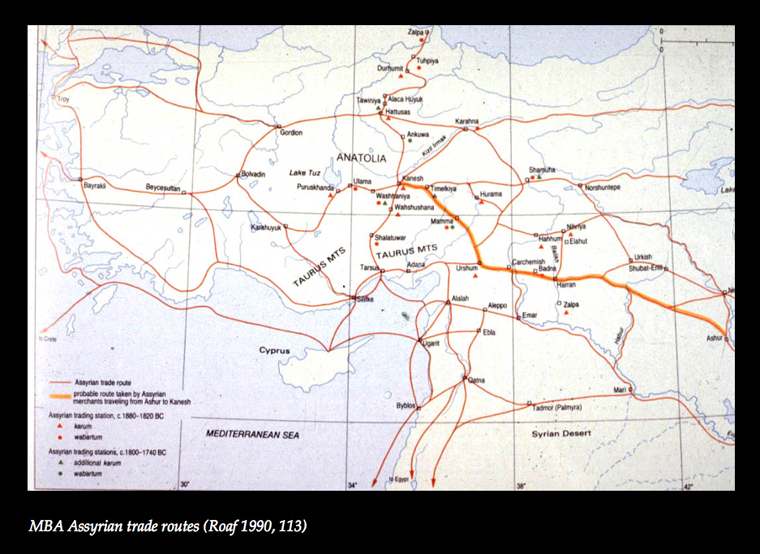

A particularly important phenomenon of the Middle Bronze Age period (already referred to in passing) was the foundation of the Old Assyrian trading centre at Kültepe-Kanesh in Central Anatolia, where the textual archive tells us of a network of larger and smaller trading stations (karums and wabartums) throughout central Anatolia and northern Syria. This must have some bearing, directly or indirectly, on the maritime centres of the northern Levant, but its effects on these have rarely been explored.

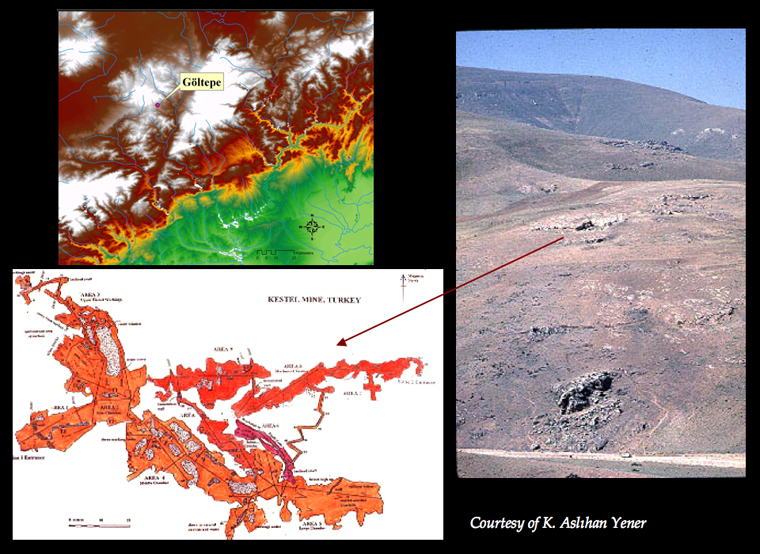

From the Kültepe texts and other written sources, we know that tin and silver were traded over long distances. The existence of silver, and possibly tin, resources in the mining district of Göltepe-Kestel in the Taurus mountains would have given an important advantage to Cilician towns situated near the interfaces of coastal and inland routes.

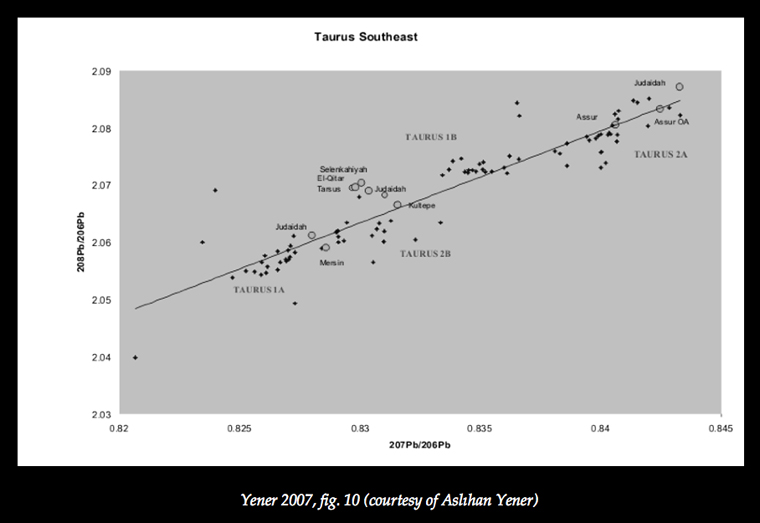

Although the claims of Kestel, as opposed to much more distant sources in Afghanistan, to have supplied tin in the Middle Bronze Age are still the subject of heated debate, lead isotope analysis of tin ingots from the later Uluburun shipwreck points to the source of this tin being in the Taurus mountains, as does isotopic analysis by Seppi Lehner of a crucible from recent excavations in the workshop quarter of Tell Atchana (Alalakh) in the Amuq (see also Yener 2003; 2007).

Strikingly, specimens of silver ore from Middle Bronze Age Kültepe and Assur in Assyria fit into the Taurus range, thus pointing to the exploitation of Taurus silver resources and their active role in long distance exchange in this period.

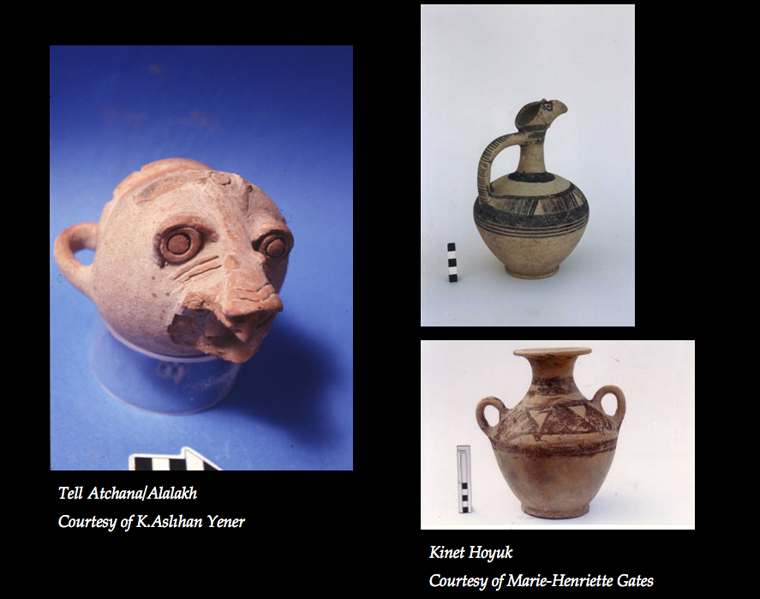

The appearance of distinct Amuq/Cilician painted ware juglets, like the one shown here from Kinet Höyük, at Kültepe in central Anatolia reinforces this scenario, as does the appearance of central Anatolian pottery (including the animal-headed cup on the left from Atchana/Alalakh) in the Amuq. The Amuq/Cilician painted wares also show close similarities with contemporary Levantine wares.

Whether it was a question of bulk or luxury commodities, Cilicia and the Amuq Plain seem to have played an important role in this Middle Bronze Age network.

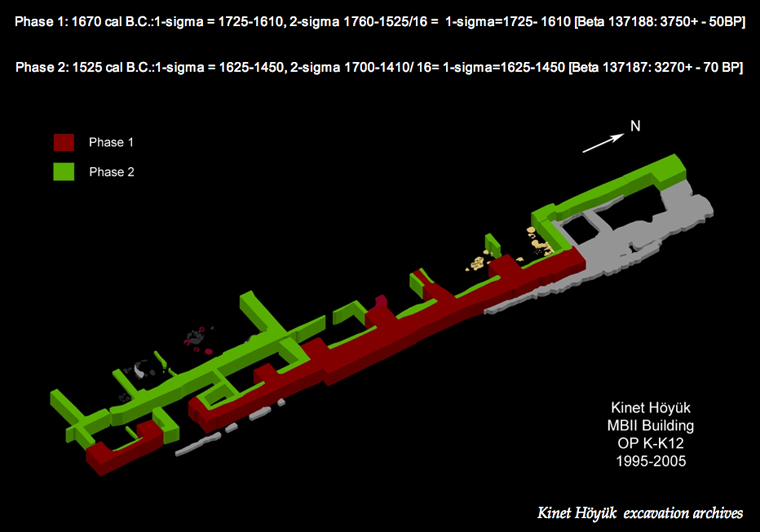

After 18 years of excavation under the direction of Marie-Henriette Gates, the site of Kinet Höyük on the shores of the Gulf of Iskenderun in eastern Cilicia is now providing extremely valuable information about the character and function of this harbour town during the Middle Bronze Age. Because of the accumulation of later levels, the Middle Bronze Age remains have been uncovered only in the eastern terrace of the site where a burnt Middle Bronze Age stratum lay directly beneath Mediaeval and Hellenistic levels.

Oriented north-south, the exposure of the storage sections of an administrative complex indicates the mercantile role of the site. This complex was reinforced by a stone tower at its northern end.

It is now confirmed that the building itself was located on the eastern slope of the Middle Bronze Age tell, and functioned as part of the city's fortification system. In the Middle Bronze Age, the palaces of the Levant and Anatolia were embedded in the fortification systems and located in close proximity to the city gates – a type of layout which seems to have a direct relationship to the control of goods going in and out of the city. The symbolic significance of the Kinet building is evident in its monumentality, and its commercial role in the large-scale depot facilities divided into separate narrow units.

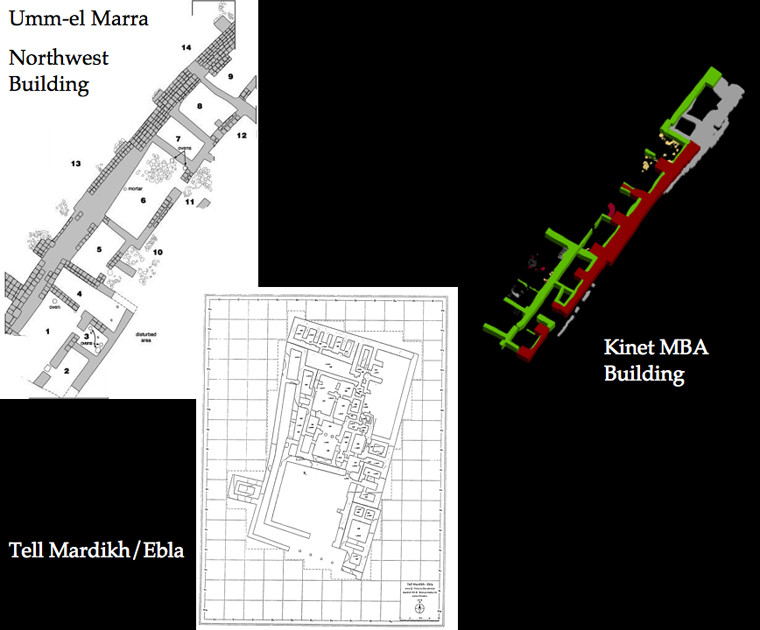

This layout is strikingly comparable with those of the Middle Bronze Age palatial complexes at Tell Atchana (Alalakh), Ebla, Umm-el Marra and other Levantine and Syrian sites.

Judging by its architectural design and use of space, the Kinet building, which is over 50m in length, would probably have exceeded the size of some of these better preserved palace complexes.

The amount of interaction between different regions of the Levant, Syria and Anatolia which is reflected in some of the pottery is also shown in other objects at Kinet Höyük, such as the mould for a duck-bill axe and a Syrian-style 'mother goddess' figurine. These may indicate that interaction between the Levantine, Syrian and Anatolian zones was not limited to trade and exchange, but also extended to the integration of foreign elements into the culture of this harbour town in eastern Cilicia.

The Braudelian approach stresses the importance of harbour towns along the Mediterranean coast as transit points along a coastal highway to provide supplies to inland centres. This perhaps also explains the small number of imported materials in comparison to local resources at Kinet, since the primary reason for its existence was not trade, as such, but the business of shipping goods. The increase in harbour town settlements along the coasts of the East Mediterranean adds weight to this idea and above all stresses the importance of maritime traffic.

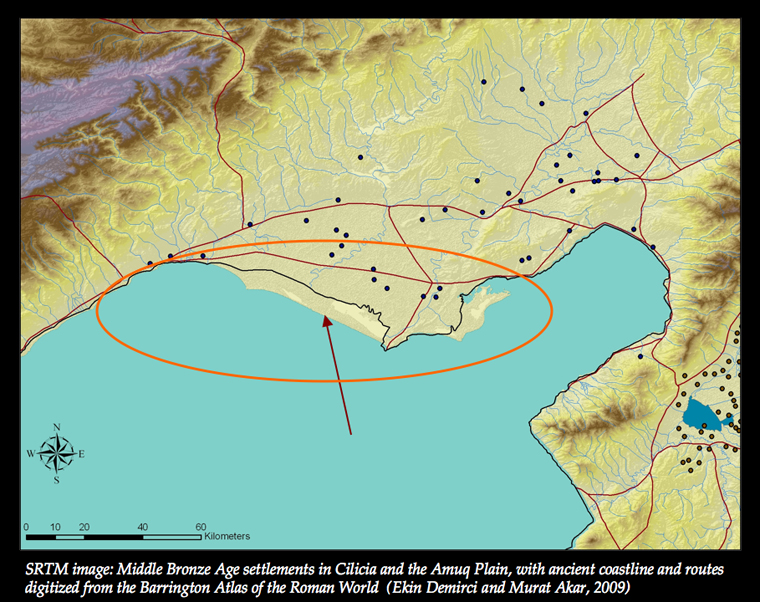

This pattern of development is particularly clear in the northern Levant and in coastal Cilicia, where the Amanus mountains restricted access between the Syrian plain and Cilicia. The mountain passes are difficult to cross and open to possible attack, and this made sea trade more practical and less dangerous. Even a relatively small site like Kinet in the 'marginal' zone of eastern Cilicia demonstrates the urban patterns of Middle Bronze II elsewhere in the East Mediterranean, and this is probably due to its external commercial interactions.

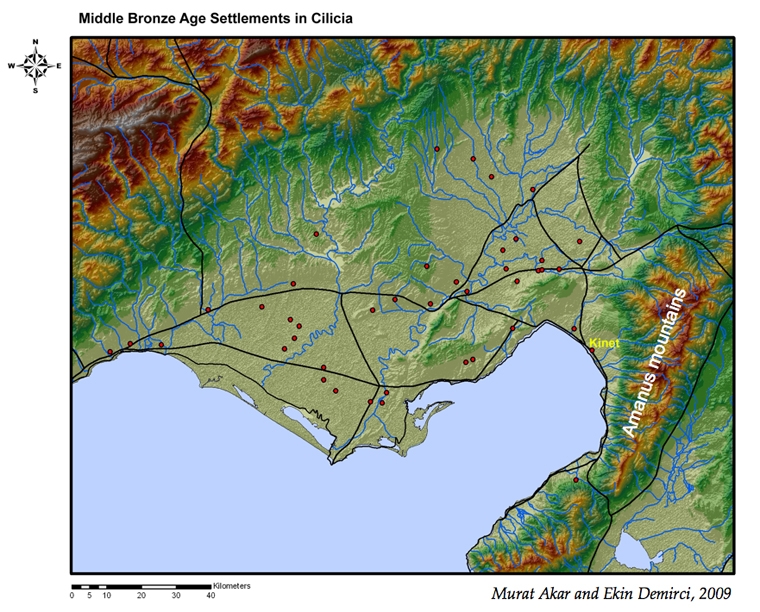

The changes in settlement pattern from Middle to Late Bronze Age in Cilicia have been analysed using GIS techniques by Ekin Demirci of the Middle East Technical University in Ankara. Based on her work, the following observations can be made:

- There is clear continuity throughout the Bronze Age in Cilicia, and there are no major changes between the Early and Middle Bronze Age although the Late Bronze Age shows an increase in settlements. The majority of the settlements in all periods was concentrated around the trade routes, which follow the coastline and pass through the mountain ranges which connect Cilicia with central Anatolia and Syria. This pattern seems to underline the mercantile nature of Cilicia throughout the Bronze Age.

The significant change in the coastline since ancient times is visible in this map, and in the Middle Bronze Age it probably lay even further north, so that settlements in the Ceyhan delta lay closer to the sea. Unfortunately, the continuing alluvial accumulations of the Ceyhan and Seyhan rivers have probably buried an unknown number of what may once have been Middle Bronze Age coastal settlements in the Cukurova (the Cilician plain).

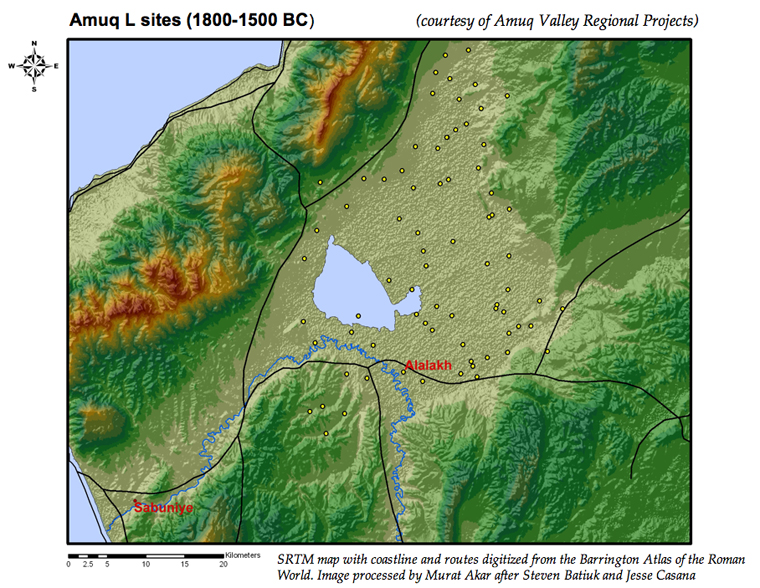

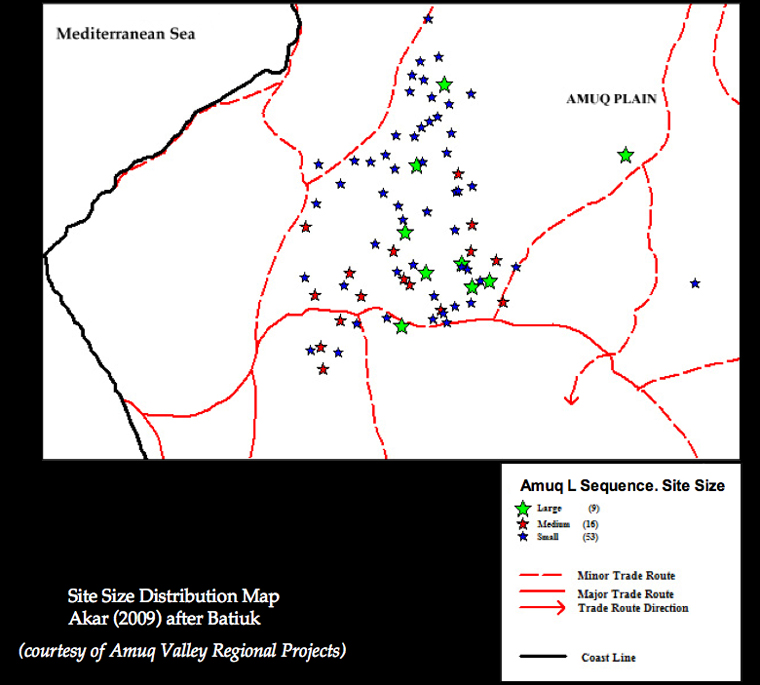

In the Amuq, the settlement patterns compiled and collated by the Amuq Valley Regional Survey Database provide evidence of a different type of organizational system, based on controlling the hinterland, with the Amuq plain itself playing a key role as a buffer zone between north-west Syria and central Anatolia, connected by means of overland and river routes. In addition, it is connected to the Mediterranean via the Orontes delta and the main pass through the Amanus, which reinforced its cosmopolitan and commercial outlook. Geomorphological changes have also affected the density of settlement remains, since rapid and frequent changes in the course of the Orontes led to frequent relocations of sites, for example around Alalakh. Alalakh itself, which during the Middle and Late Bronze Age was the capital of the Mukish kingdom, is located in a very advantageous position, with access to the major land routes from north, east and south. Its close connection with the site of Sabuniye at the mouth of the Orontes gave it the character of an inland harbour.

The Middle and Late Bronze Age Mukish kingdom was a territorial kingdom, focused around a number of small agricultural sites nested within a hierarchical system of medium-sized and larger sites. Here we can see the site-size distribution for the Amuq L period (Middle Bronze Age), with a network of larger sites dotting the landscape of the plain to the north and north-east of Alalakh.

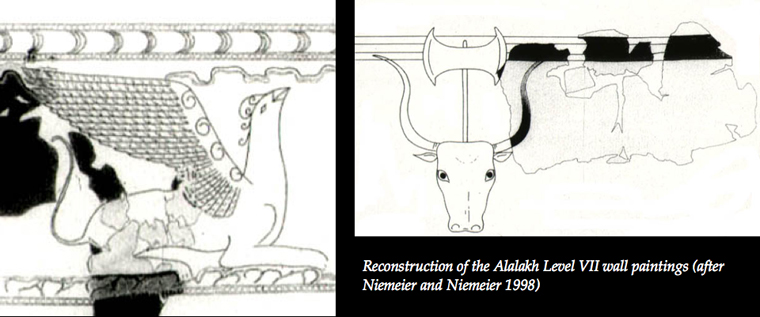

The excavations by Sir Leonard Woolley at Alalakh in the late 1930s uncovered wall paintings in the Middle Bronze Age Level VII palace, which were compared by him to those of Minoan Crete.

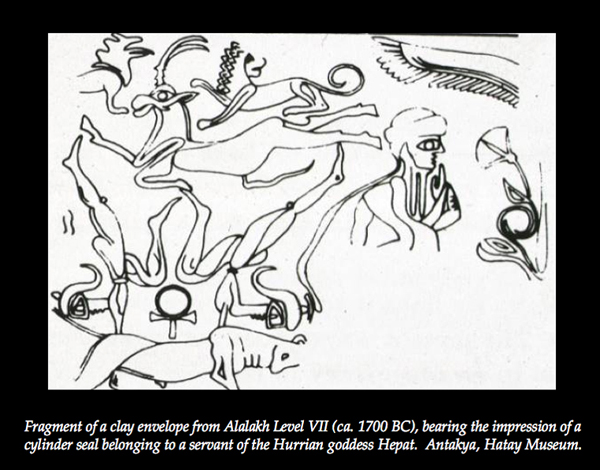

A cylinder seal impression, from a seal belonging to a servant of the Hurrian goddess Hepat, includes a scene of bull-leaping, an iconographical element also known from Crete. Recent excavations, going further down into the Middle Bronze Age levels, are now providing more information about Alalakh's role in wider systems of interaction.

The appearance of Cypriot White Painted V pottery in the eastern part of the tell, separate from the palace area, provides evidence for very late Middle Bronze Age connections.

Similar material is found at the contemporary site of Tell Tweini, in the coastal plain of Jebleh in Syria, where the commercial role of this harbour town is emphasised by its maritime contacts wih other regions of the East Mediterranean (especially Cyprus) at this time. More excavation and survey in the coastal plains of the northern Levant and Cilicia will expand our knowledge of Middle Bronze Age commercial interactions. Current evidence already indicates the international nature of this period and its impact on the formation of Middle Bronze Age urban centres. This is visible in internal site patterns, including fortifications and monumental architecture with depot facilities, and a variety of imported goods and materials. On a regional scale, it is visible in the build-up of centres in proximity to major overland and maritime routes.

This aerial photo of Kinet Höyük, showing the oil and gas shipment terminal next to the site, demonstrates something of the continuity of its strategic location for commercial activities since the Middle Bronze Age. When this photo was taken, shortly after the start of the Iraq war in 2003, the economy of the district had been dramatically affected. The parking areas, which formerly held hundreds of trucks, were virtually empty, the oil tankers at the docks had almost completely vanished from the scene, and the place was buried in silence. The disruption to the oil-shipping business had its impact on the wider economy, and many shops, restaurants, barbers' shops and other small traders – as well as oil and drug smugglers – packed up and disappeared after less than a year of crisis. It is perhaps from this sort of economic and commercial perspective, in which disruptions in one region can have repercussions in others within a linked network, that we ought to approach the phenomena of urban collapse and regeneration in the Bronze Age.

Occasional Papers (2009-)

Occasional Papers (2009-) Site Visualisations

Site Visualisations