Here we examine the traces of ancient route systems in the Ancient Near East according to:

- Their pattern

- Processes of formation

- Parallels elsewhere

- Their function

On the ground

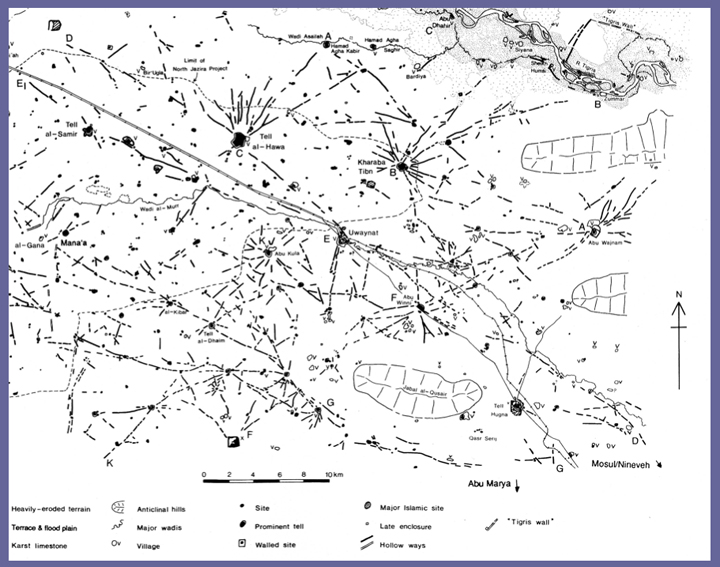

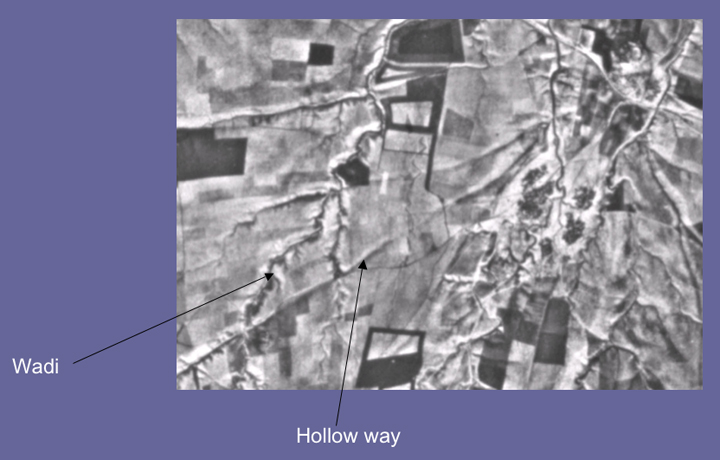

A particularly common trace of ancient route systems on the ground is the 'hollow way'. In the Middle East hollow ways, like their counterparts in the UK & Europe, appear as long, usually straight valleys.

'Hollow way' leading NW towards the major city mound of Tell al-Hawa in NW Iraq.

Tell al-Hawa from the SE.

In the images above, the massive city mound of Tell al-Hawa forms the focus of a radial system of hollow ways that remain primarily on the northern side of mound (as indicated by black lines on the map). Note how the hollow ways fall into two groups: a) radial systems and b) longer, cross-country systems

Satellite image of the hollow way SE of Tell Hawa in Northern Iraq from Google Earth.

Sadly, as is evident on this recent satellite image seen above, many hollow ways are now mainly in-filled and eroded as a result of long periods of ploughing.

Processes of formation

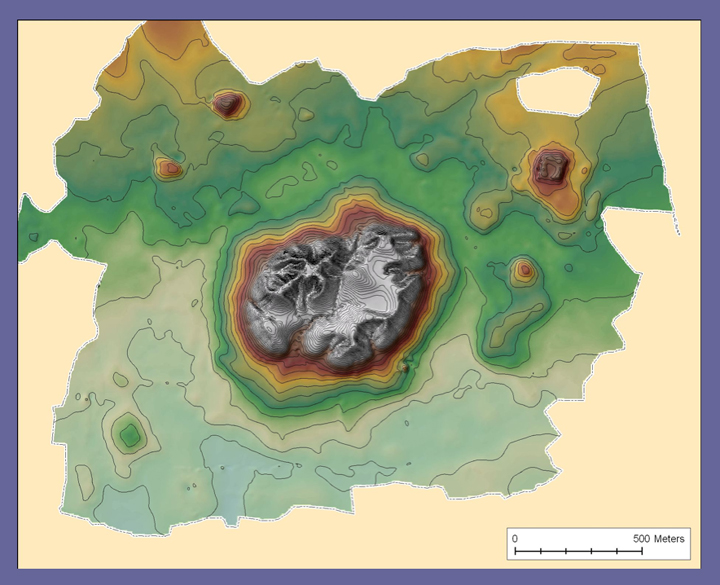

Tell Brak, NE Syria, has been excavated since 1975 under the direction of Professor David Oates and Dr Joan Oates for the British School of Archaeology in Iraq.

Tell Brak, like Tell al-Hawa, formed a major nodal point in the landscape for thousands of years.

Map by Tim Skuldbøl and Torben Larsen; courtesy of the Tell Brak Project (many thanks to Dr. Joan Oates for permission to use on the ArchAtlas web site).

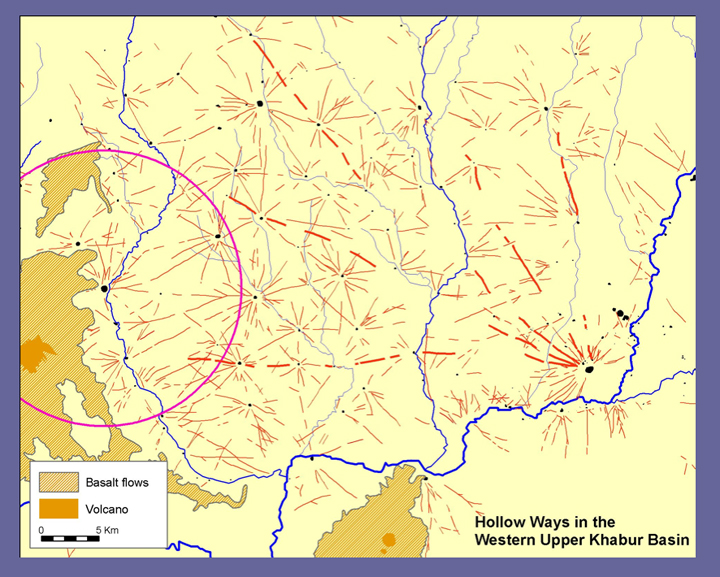

Hollow ways, at least locally, increase drainage density & channel length. Map by Jason Ur.

Note in the image above how the hollow ways around Tell Brak and neighbouring sites form radial networks with occasional cross country routes.

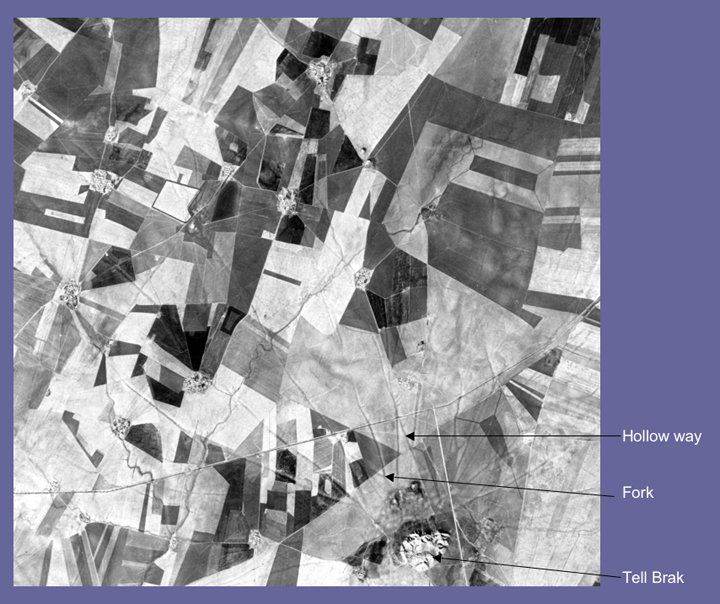

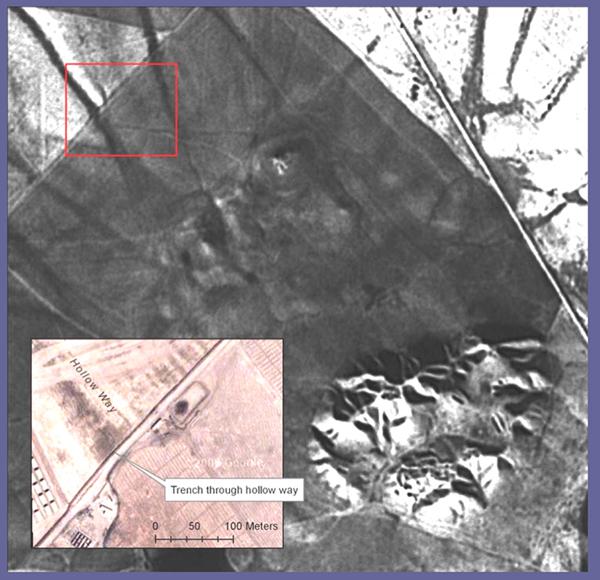

On satellite images such as this CORONA image above from the late 1960s the hollow ways appear as distinct broad grey lines with occasional forks at 1-2 km from the tell.

By kind permission of the Tell Brak Project.

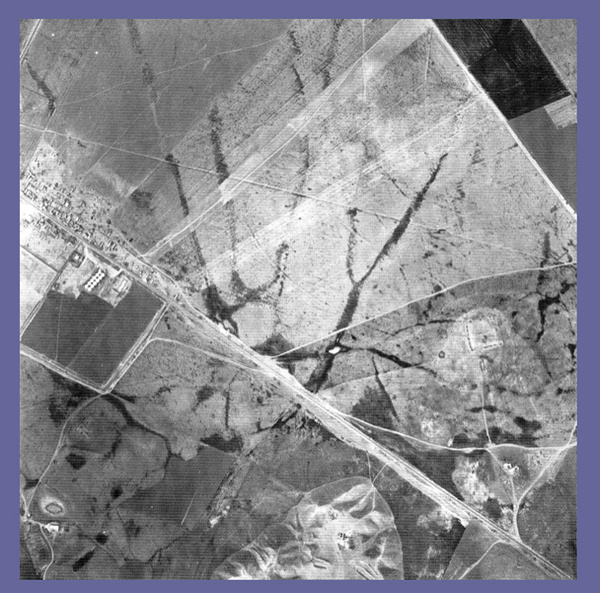

On this oblique air photograph (seen above) taken by Prof. Dr. Hartmut Kuhne, hollow ways to the NE of Tell Brak form a clear radial pattern.

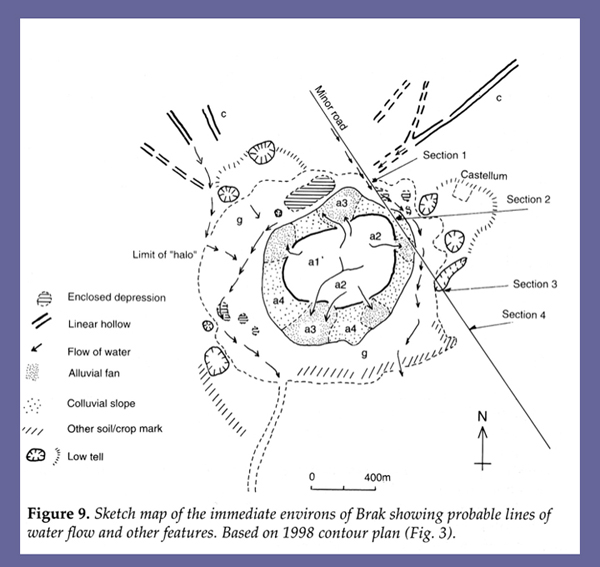

Figure 3 from Wilkinson et al. 2001.

A distinctive feature of Tell Brak is that it is surrounded by a curious 'halo' which appears to have included a number of pits excavated to supply soil for making mud bricks. Hollow ways appear to have gathered water from a hydraulic catchment to the north of the site and to deliver it into the halo around the site.

Before interpreting hollow ways it is necessary to describe and record them.

Corona image by courtesy of the USGS. Processing thanks to Jason Ur.

Here, in the image above, a well-defined hollow way (within red rectangle) was seen in 2005 to have been cut by a machine-dug trench.

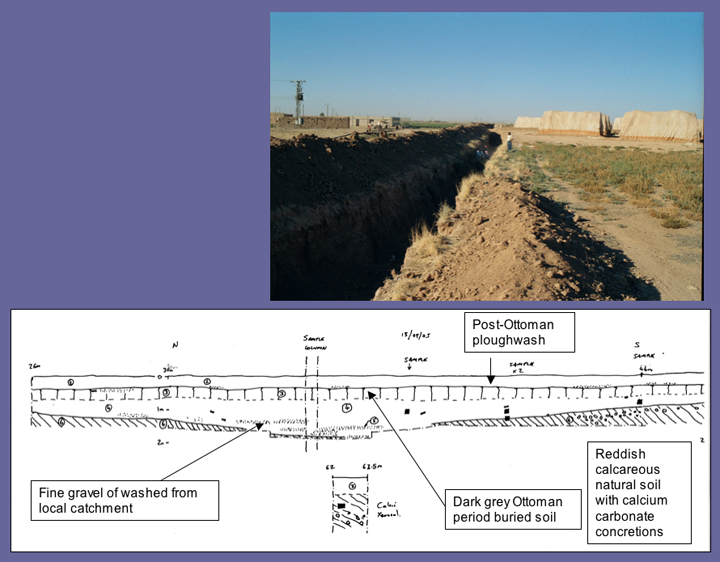

The hollow way at Tell Brak is defined by a broad vegetation mark (top). The 20m long field section shows the sequence of sedimentary within the hollow.

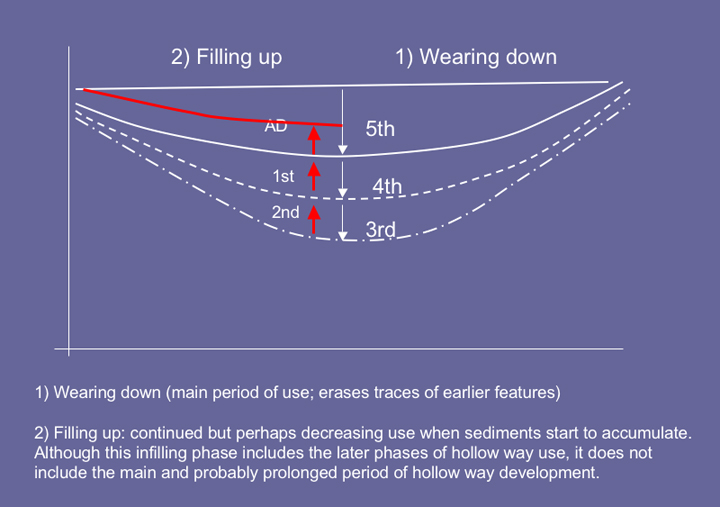

Hollow ways do not appear to be dug features, but rather are worn into the ground surface. As a result it is difficult to date their formation which consists of a long period of wearing down as indicate on this diagram above.

Khabur Basin: Hollow ways as hydrological networks

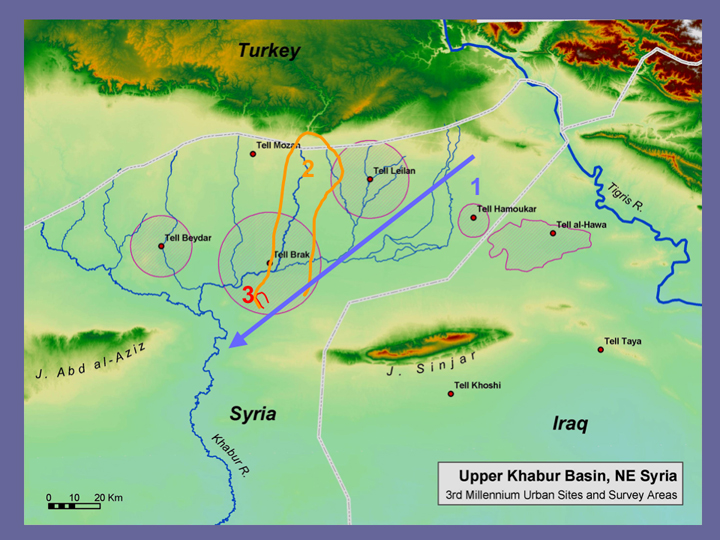

Just as modern tracks and road conduct and channel storm runoff, hollow way routes also channel flow from the immediate hydrological catchments. As a result of their mineralogical composition it is possible to identify the source of the constituent grit and small stones contained in the hollow way fills.

In the wadis and channels around Brak 3 groups of sediments have been identified:

- Pleistocene, far travelled, with gravels from Anatolian source (only evident in some wadis and Pleistocene terraces).

- Wadi Jaghjagh gravels, consisting of rolled gravels, mainly limestone.

- Local, slightly rolled, calcium carbonate nodules, typical of hollow ways.

In the image above, the three main classes of catchment are sketched on the map of the Khabur basin: 1: Anatolian rivers (blue) 2: Jaghjagh catchment (orange); 3: field catchment (red).

Northern Iraq: Hollow ways and the drainage net

Not only do hollow ways conduct some overland flow, they also feed it into existing channels thereby accelerating their development.

The air photograph above shows radial hollow ways around a tell in NW Iraq that feed into small meandering wadis. Also see Tsoar & Yekutlieli 1993.

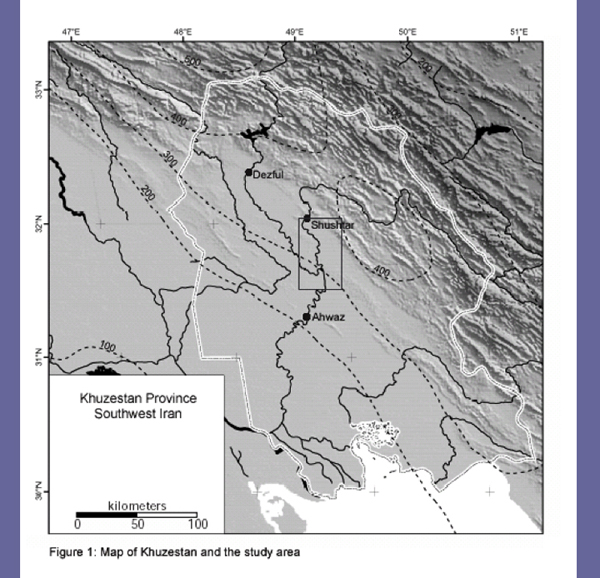

Channel changes in SW Iran: an example from the Susiana Plain.

From Alizadeh et al. 2004. The University of Chicago Project to SW Iran, directed by Dr. Abbas Alizadeh, Oriental Institute. Thanks go to Mr. Mohammad Beheshti, Jalil Golshan & Dr. Massoud Azarnoush of the Iranian Cultural Heritage Organization.

Tracks, paths and erosion

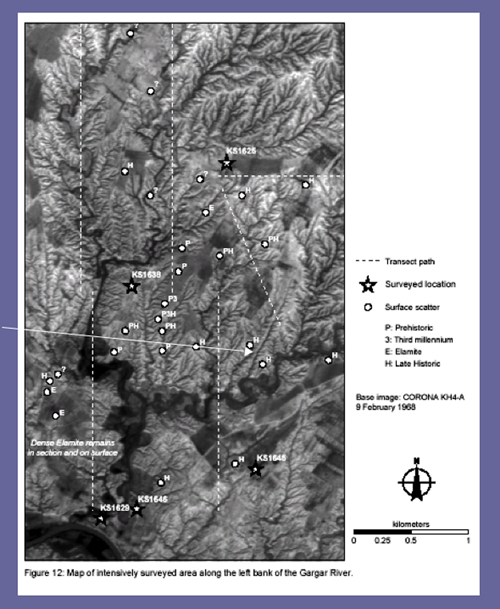

Corona image processed by Nick Kouchoukos.

The eastern plains of Khuzestan near the Gar gar River exhibit extensive badlands of recent date. Some of the gullies appear to have eroded their way back along former track ways leading from archaeological sites.

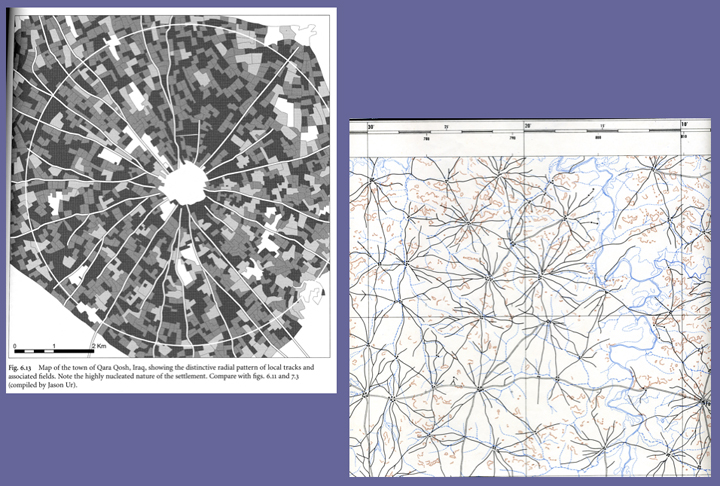

Radial routes can also be found around modern settlements. Image to left is the town of Qara Qosh, Iraq (Wilkinson 2003) and image to right shows cattle trails around villages in southern Mali / northern Ivory Coast, West Africa.

The considerable width of ancient hollow ways in the Near East suggests that they were not simply roads for pedestrians and wheeled vehicles (although both did contribute to their development). They also resemble certain types of broad drove ways evident in Britain and parts of Europe such as the sheep migration tracks in the mountains of Italy:

'These great grassy arteries utilized for the transferring of flocks of sheep and goats and herds of cattle from the pastures of the plain to the pastures of the mountains, had a width of 122.02 yards (111.60 meters), a standard width that permitted the flocks to graze and migrate without problems.' (Angelo 2002).

'The broad tracks – some of them still largely visible today – were one hundred and eleven metres wide and might be as long as seventy kilometres; they were marked by the passing and repassing and grazing and resting of thousands of beasts each year.' (Emiliani 2003-6)

Conclusions

Hollow way systems in the Fertile Crescent are generated, in part, by movement of sheep, side-by-side. Humans walking to their fields as well as wheeled vehicles also contribute to their development. They are accentuated by fluvial erosion, usually, but not necessarily, from local catchments. Part of a nodal pattern of movement around focal points of long duration (such as tells). Parallels occur from UK to Africa. Note, the nodal structure determines pattern and processes influence scale.

Occasional Papers (2009-)

Occasional Papers (2009-) Site Visualisations

Site Visualisations